Questions: a response to Tanja Woloshen and Deanna Peters’ Research

By Callie Lugosi

“I need more arms.”

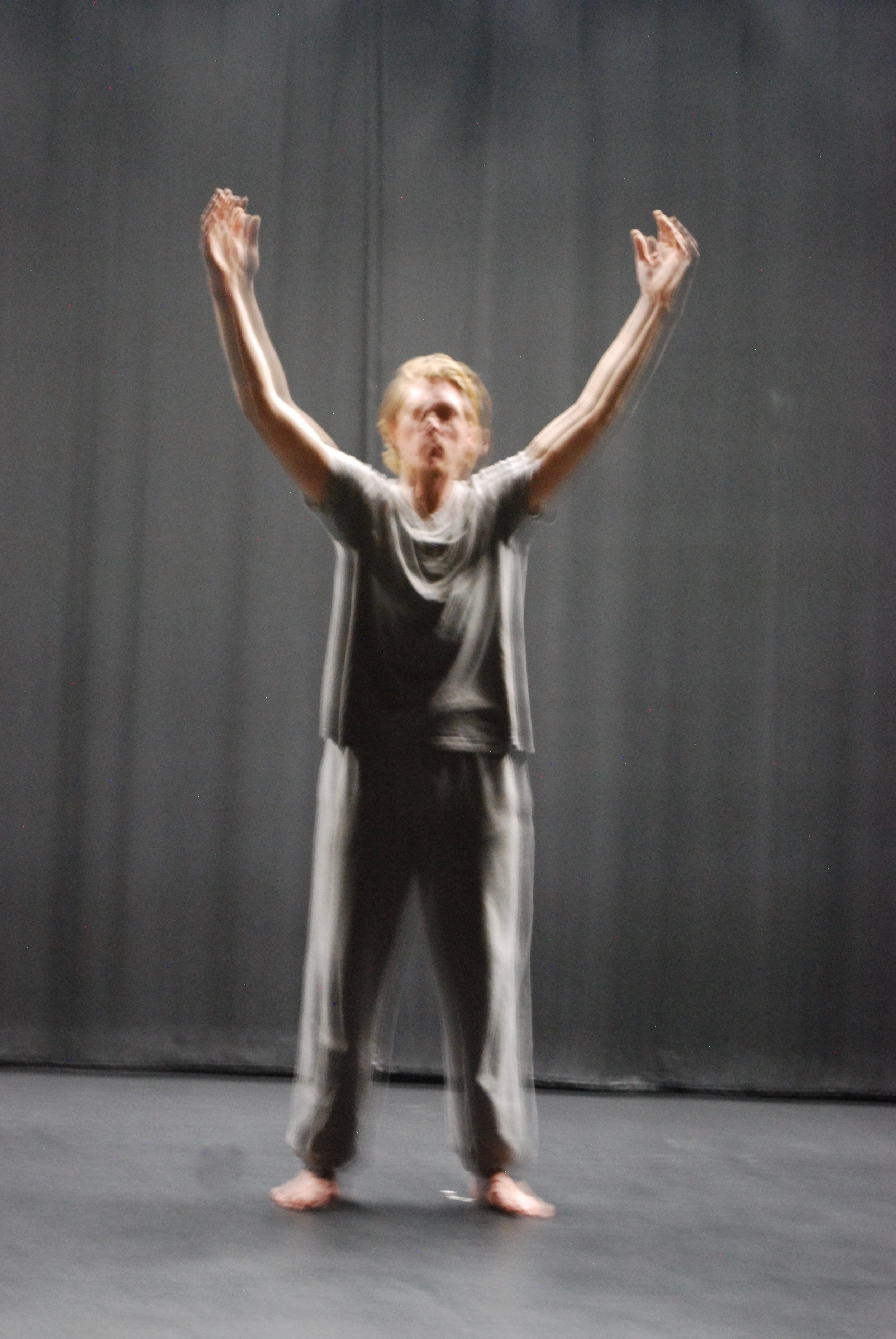

In Tanja Woloshen’s research, she raises questions such as: What is the body? How could

investigating limb consciousness inform ecology and freedom? What do our limbs carry? How do I explore our relationship to the future through the body?

These questions are big and esoteric in nature. When asked to clarify what she’s exploring and finding in asking these questions, Tanja said this:

“These questions, honestly, are very intuitive. I’m just beginning my foray into what I’m researching. If I start to investigate these questions of limbs, does that open potential for connecting to the earth? If I’m just thinking about stuff or thinking about myself, if I start to question or investigate what’s happening there, does it change the relationship? It’s philosophical, but I don’t really have answers to these questions yet, they’re very open ended questions.”

On “What do our limbs carry”:

“That is an ongoing, essential question that continues to orbit and don’t have any answers to it.

You know when you’re going about your day and you’ve got all these bags? Like, you’ve got your computer bag and textbook bag, and you’ve been to the library and you’ve also gone to Sobeys, and I’m always like, ‘I need more arms.’”

“It began with considering what our limbs are physically carrying, but also what do we need to let go of, what are we holding on to spiritually or practically, psychosomatically, what are we carrying and what we are holding onto … This was kind of the impetus for the question.”

“These questions are still clarifying as I’m working. They’re these big, overarching things that need an immense amount of clarification as I dig into the process. When I say “our”, I’m thinking “our” in terms of human, but of course I’m coming from only my perspective, my portal … It’s part hypothesis and part science fiction, how we as humans, potentially relate to the world and to the earth through the human body, and what potentially might morph and take shape over time.”

“I want you to hold the angry part.”

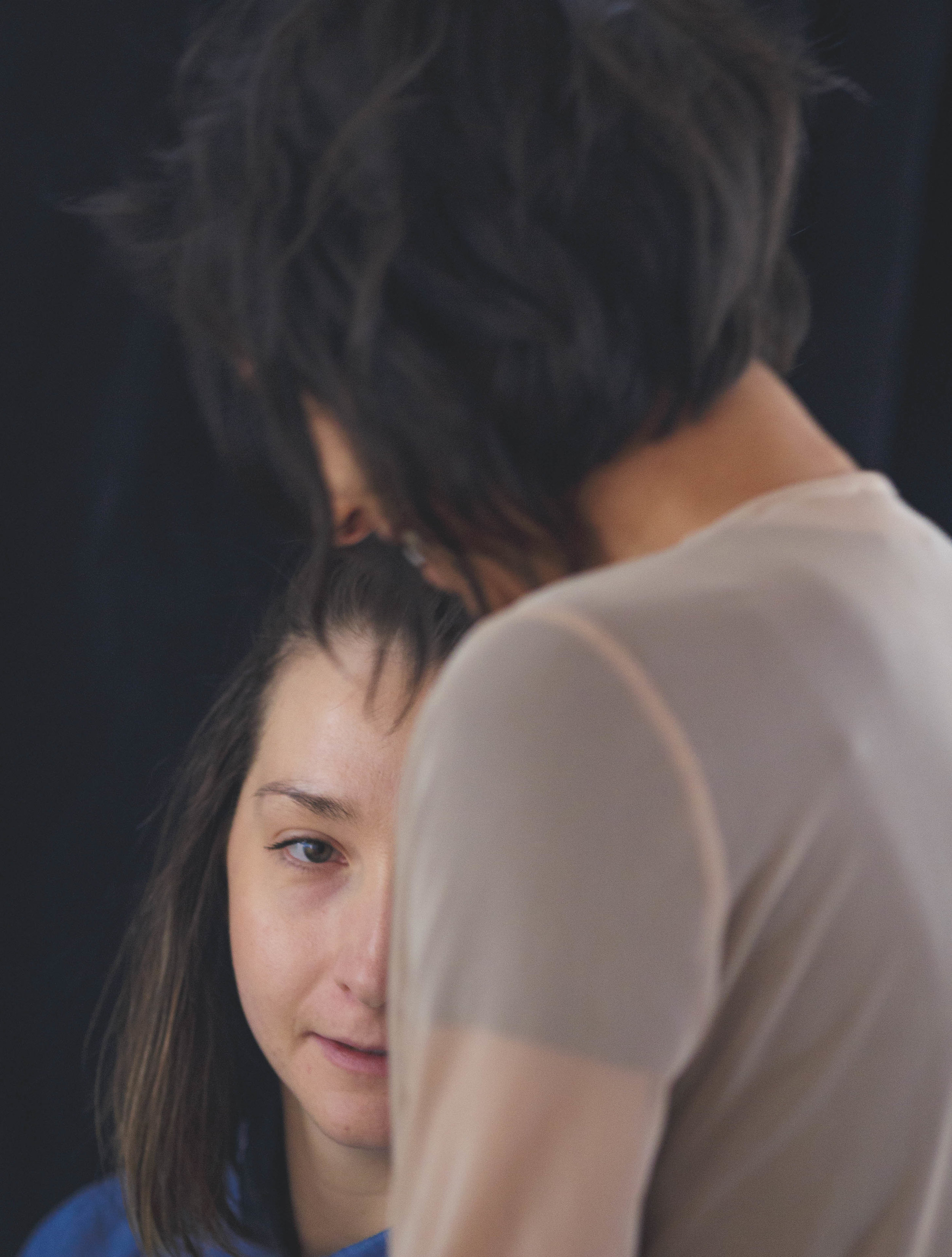

In Deanna Peters research, they question the form of the duet. What happens when we turn our gaze to one another? What sorts of impulses arise from this intimate state of seeing and being seen? What kinds of spaces do we create together? How does this focus on each other invite others to see us?

On ‘What part of your body do you want someone to hold’:

“We’re talking about how to take it from something that’s very literal and physical that has mass in space and thinking about releasing part of your body that’s causing tension, this sort of thing,” Deanna says. “Yesterday I said to Less, ‘I want you to hold the moody part of my body’, which leads it into a more abstract exploration.”

“In terms of the audience, I’m interested in our shared experience. Although, not everyone’s body is the same, there are things that we share. If I say ‘I want you hold my jaw’, I feel like it connects energetically through the parasympathetic nervous system, or mirror neurons. It asks the audience to consider their own jaw or their own body.”

“There’s a transmission that happens though the audience witnessing our experience, and invites our questions into their own minds, because they are seeing us problem-solve them in the moment. When I say to Less, ‘I want you to hold the angry part’, he’s literally looking at my body and deciding in that moment what to do, and they’re seeing that happen live. It’s like we’re all thinking together in a way, and maybe our thinking will diverge, but there’s also the satisfaction in seeing what we come up with live in the moment. It doesn’t come across as hyper sentimental or organized in a way that’s supposed to pull people’s heartstrings.”

On ‘What kind of spaces do we create together’:

“(Less and I) do this thing called mirror touch where we are creating a symmetrical center. The shapes that come and go are kind of psychedelic, in a way. Through an effort to be symmetrical, we reveal an asymmetry as well. There’s energetic space too, and for lack of a better term, aura. Where does our body end and where does it begin?”

“With intention, (we’re) considering how we can hold that connection energetically. In one part we’re quite entwined for a period of time, and then we really slowly move apart from each other. What we’re trying to do is try to stay connected even though there’s distance between us is becoming greater. That also triangulates with the audience because each one of them have a perspective on the shapes between us or the shapes around us.”

“I gutted the living room.”

I pushed myself to personally explore a few of Tanja and Deanna’s research questions, in particular ‘How do we experience the future through our bodies’, ‘What do our limbs carry’, ‘What part of your body do you want someone to hold’ and ‘What kind of spaces do we create together?’

Unsure of how I would approach personally answering such abstract questions, starting with a stream-of-consciousness style of writing seemed appropriate, if only to see what ended up on the page. I got comfortable and let go for a bit. Entering a weird calm, I held the aforementioned questions at the front of my mind, with the output coming from as far back as I could channel it.

The advice that Tanja gave me was to ‘just trust the work’. I took this to heart.

When I stepped back to look at what I’d done, I realized that I’d written a piece that, more than anything else, resembled a script. It was instructional in the way that script is, but it told a story.

This is the unedited draft of that writing:

“I gutted the living room.

Standing squarely in the middle of the space, I surveyed the room and decided what to do first. First I took the curated selection of coffee books off the table, the potted plant and the art deco cigarette holder and ashtray and put them on the floor, exposing the naked surface of the coffee table.

I wiped it down slowly and with intention, careful to not push the light dust of soil from the potted plant onto the white carpet. Lifting the table onto my shoulder, I portaged it out of the living room, down the hallway and into my bedroom.

Next I rolled up the carpet and did the same. Then the couch, bookshelves and hundreds of books, onward ad nauseum until the room was completely empty, except for me and dust.

Sitting squarely in the middle of the space, I waited. I asked my body questions. It started as a whisper and the more I listened, the louder it got and the more I learned.

Something it said:

“The only one that could ever really know me is you and if you don’t try, then there is a possibility I could die not knowing what it’s like to be loved,” it said. “I don’t want to die like that.”

We continued to talk. We renegotiated our relationship, established boundaries, forgave each other.

We talked about our future.”

Creating that piece of writing felt like the real and literal response. Given that it was the first output I’d produced so far, it felt inspiring and hopeful. There was something to this.

I felt compelled to pursue it in a literal way for the sake of what I’d been commissioned to write. I felt that if I could do this work, I could produce an authentic and deeply personal response to the artists in residence’ work. The thought of filming it and cutting it together would make for an interesting and convenient presentation at the endnote, given my distaste for public speaking.

I did the thing.

I filmed myself following the prompts this writing was guiding me to do. Over the course of several hours, I methodically took the living room apart and sat in the middle of the room and waited.

I felt nothing, and then completely disillusioned.

Why didn’t the right thing happen?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Upon reflecting on what I’d written and performed and the failed experiment therein, my interpretations and answers to Tanja and Deanna’s questions became clearer. It was apparent that two questions in particular resonated with me the most.

From Deanna, What part of my body do I want to be held?

My interpretation of this question concerned the conversation I wanted to have with my own body, and making and holding space for my body to communicate its needs or desires. The question led to another: what do I have to do in order for this to happen?

This was explored further, through my interpretation of Tanja’s question: ‘What do our limbs carry?’

We, and by extension our limbs, carry our possessions and rearrange them, to clean and curate the spaces we inhabit in order to feel in control and more comfortable. I took those means and used them toward a different end. I wanted to pick up my entire living room, not for the purpose of cleaning or rearranging, but to create a new space that existed solely as an arena for my internal dialogue to take place. What would I discover if I situated myself in a space removed of all worldly purpose?

My hope was that, by taking the ‘living’ out of my living room and temporarily freeing myself of that perpetual need for control, I could allow myself time and space to explore Deanna’s question: ‘what part of my body do I want to be held?’

I still have questions.

Why didn’t this work? Am I really so ignorant of my body and how it works, feels and interprets stimuli that I couldn’t produce the results I set out to achieve? Is introducing my body into my writing and visual arts practice in a very literal way simply not for me? What even is my relationship with my body? What is my body’s relationship with space? The space I live in? Where do I end and where does my body begin, and if there is a wedge between us, where did it come from? Are we the same?

When my experiment didn’t deliver the results I sought out to achieve, I realized that dance, and all art by extension is just asking a lot of questions that, more often than not, lead to other questions.

Allowing space for experimental methods of inquiry is at the heart of the Young Lungs Dance Exchange Research Series. It creates opportunities for artists to creatively question, but it also opens up conversations around bodies in movement to the greater community. Through workshops, presentations, and endnotes, people are given opportunities to explore their own movement theories, to challenge what dance is, and ask hard questions about the body.

The following questionnaire functions as a springboard for probing deeper into the significance of movement and our relationship with our bodies, and the place in time and space we occupy. It is also a meditation on the act of question-asking itself.

Questions beget more questions.

Introduce yourself.

Do you consider yourself to be a creative person?

How do you make space for yourself?

When was the last time you communicated with your body? What happened?

How do you experience your gender identity through movement?

Whose gaze do you appreciate most and why?

How does other people’s perceptions of your body inform the way you move?

How do you make space for other people?

What do you notice most about the way other people’s bodies move?

Can you be more specific?

How does history inform the way you move?

When was the last time you danced for or because of someone else?

How do you experience your relationship to the future through your body?

How aware are you of the physical space you occupy, everywhere you go?

Why do you think that is?

How much do you forget? Where do you think the forgotten stuff goes?

How much do bodies remember?

What is your body’s relationship with nature like?

What part of your body would you like someone to hold?

Are you your body or your mind?

What is a body for?

seeing and knowing

by hannah_g

Produced as part of Research Series September-November 2017

I was looking at some reproductions of Torey Thornton’s paintings the other day. Colourful, witty, the paintings contain forms which correlate to things in the world one may be familiar with – tiger stripes, fruit, a herd, furniture. Getting into their specifics, however, places one in the realm of conjecture. Is the tiger dead or alive or someone in a tiger suit? Is that blob a table or a rug? “His work oscillates between legibility and abstraction,” as the Almine Rech Gallery puts it. This oscillation – which occurs across many disciplines – provides the means for recognition, alienation, self discovery, enjoyment, connection, boredom, distraction, contemplation … that is, it provides a means of exchange.

.

Alexandra Winters & Warren McLelland

*

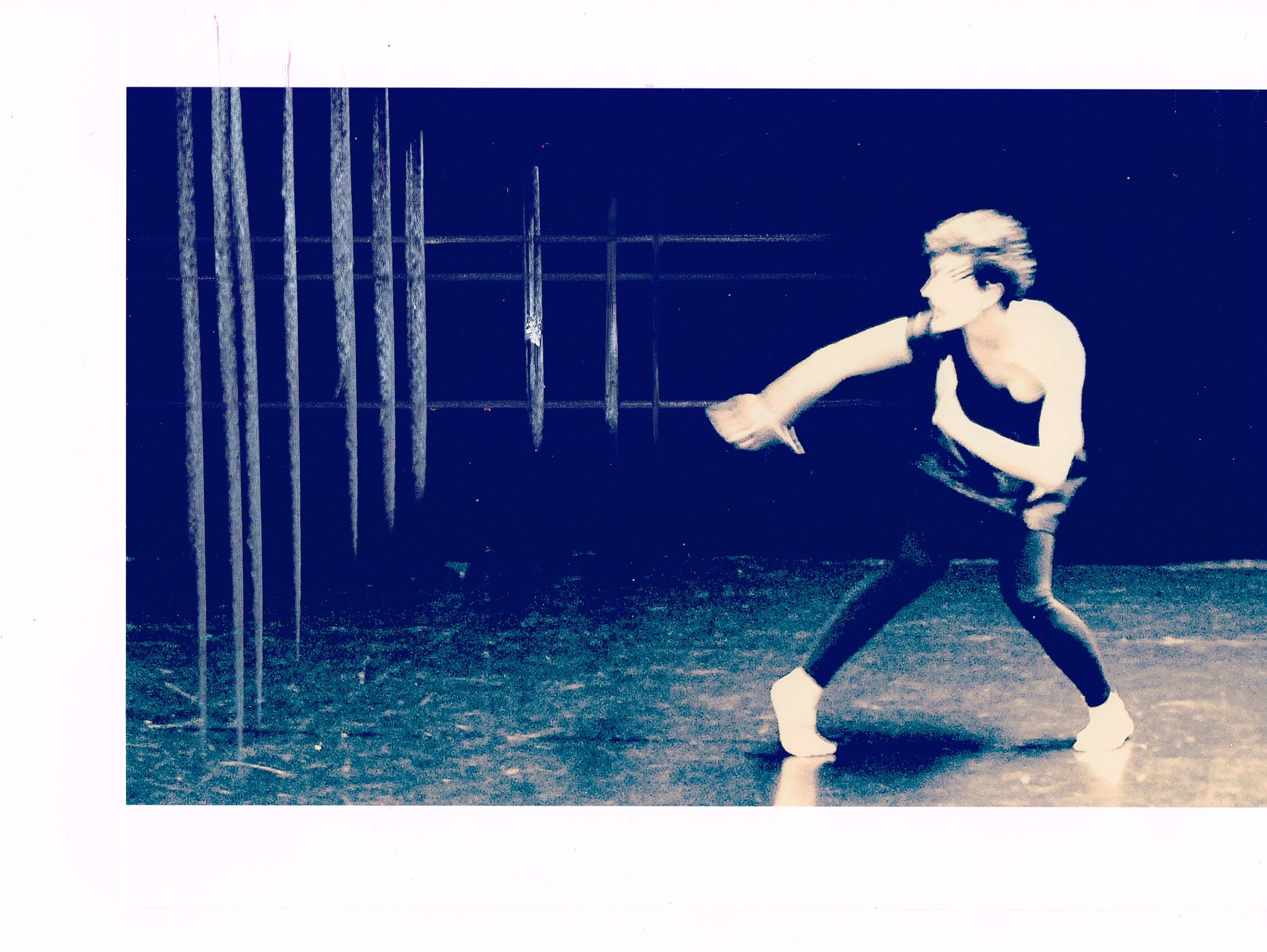

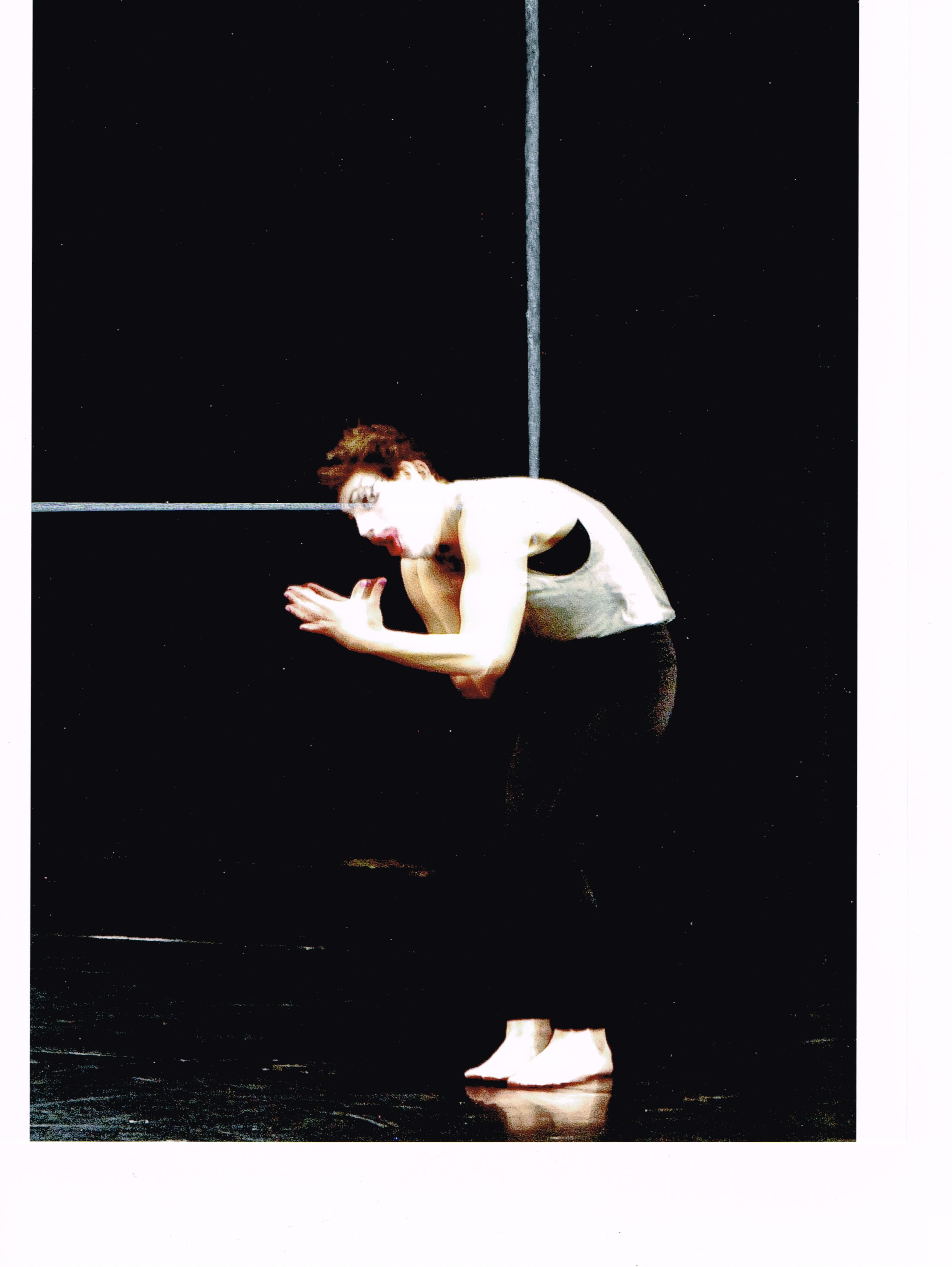

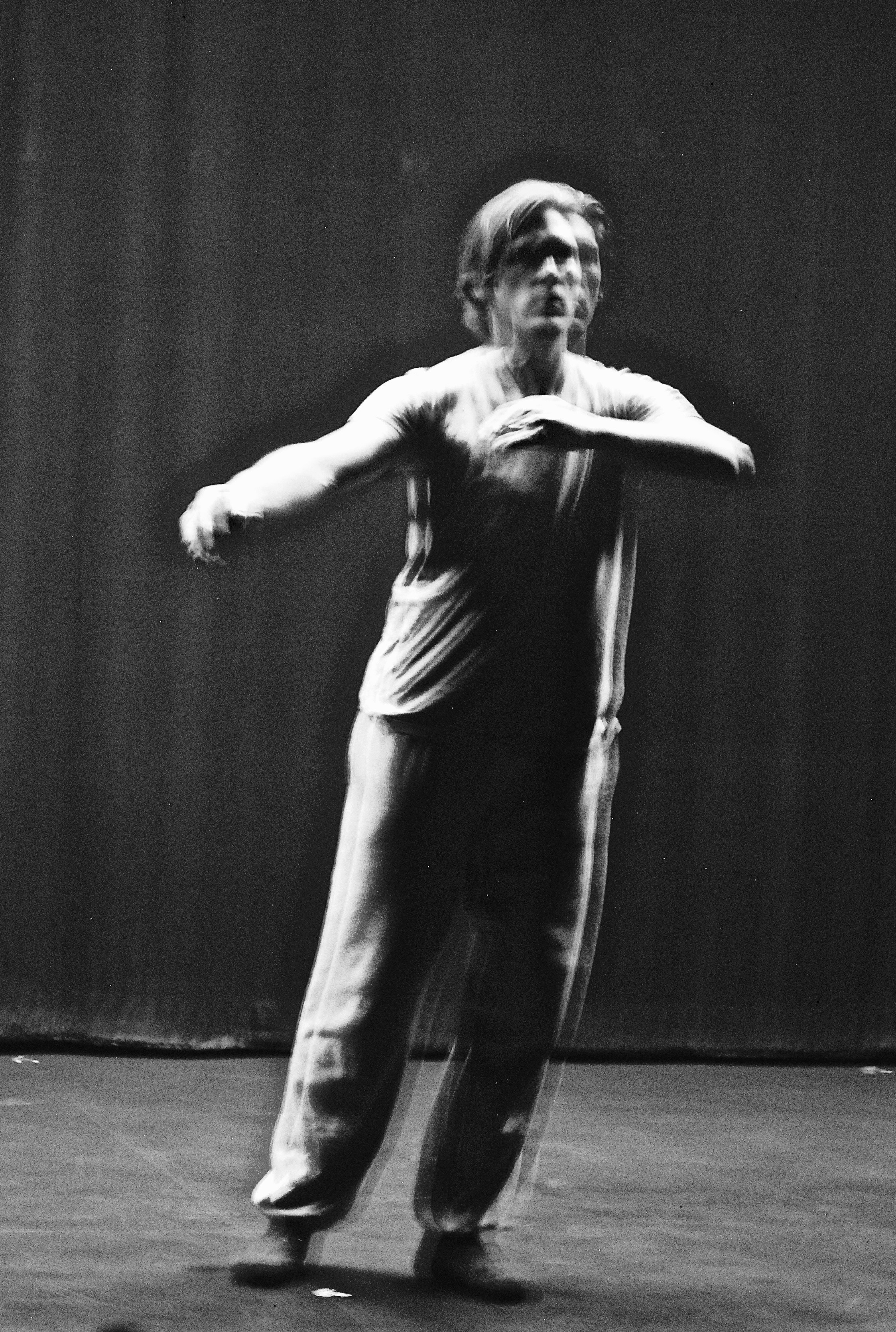

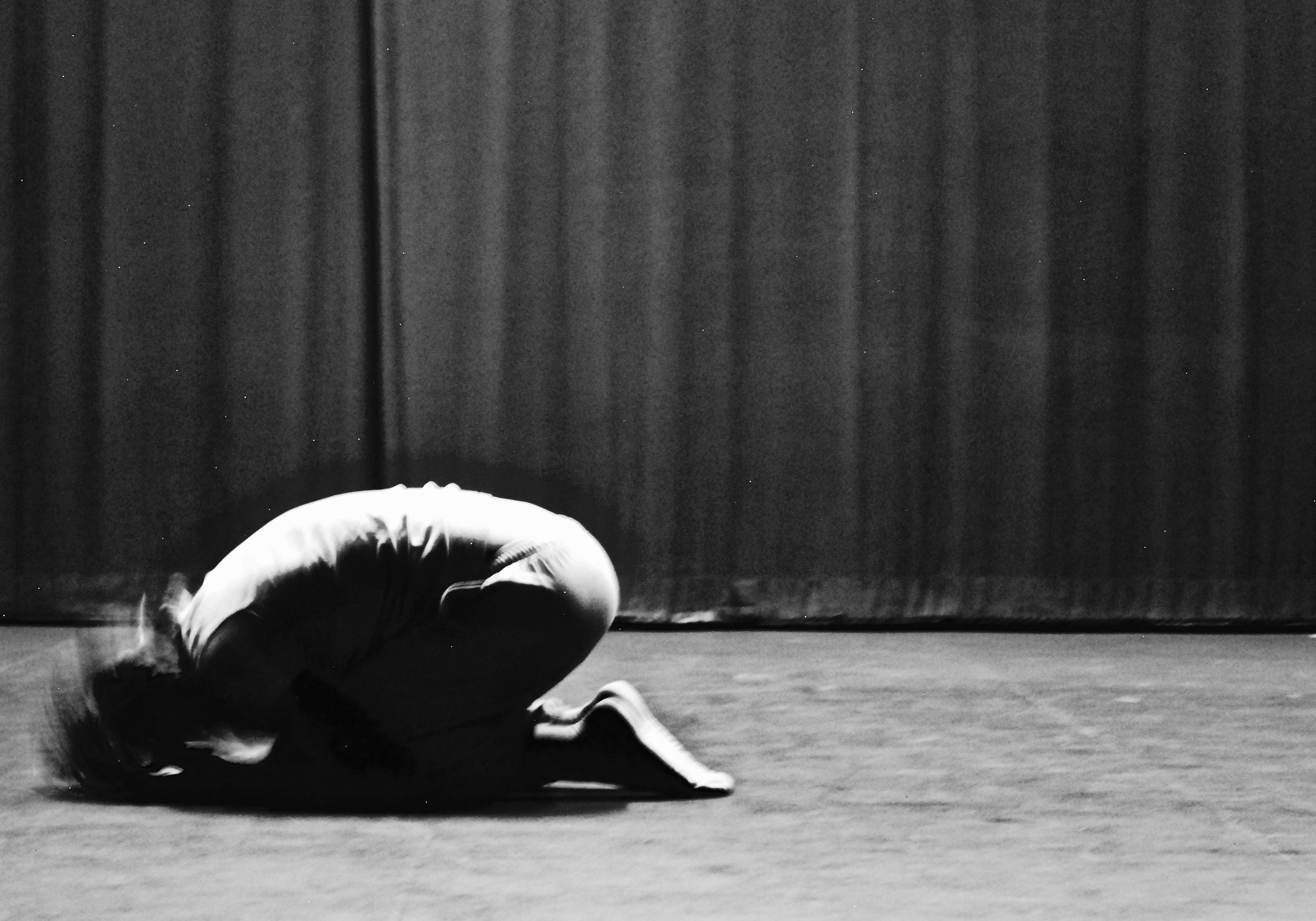

Speed, strength, stamina, and repetition are common elements of sport and dance: Winters’ choreography on McLelland and herself sought the crossover between the two and thereby perhaps the epiphany of a common intention.

The cheers from a huge crowd was the work’s soundtrack and accompanied McLelland’s warm up jog which stopped abruptly at one of the studio’s pillars (amongst four of which the piece was placed to infer a sporting frame such as a baseball diamond, the corner of a soccer field, or a ring). Here his body opened into the star shape that often accompanies a sporting moment, such as when a soccer player strikes the ball for a long punt or baseball fielder is in the air straining to make a catch. For the duration of the first half of the piece, McLelland referenced a cluster of sporting gestures from soccer and football players, baseball shortstop and batter, ice hockey goalie, and referees, which the choreography stylised, decontexualising them so that aggression, efficiency, and the need to win made way for a physicality that elicited other references that included voguing and ballet as well as moments that fell entirely out of specific techniques. Winters, dressed in the black t-shirt and shorts most readily associated with referees, signified the second half. Offsetting the ref reference, she engaged McLelland combatively, emulating the intimate, non-sexual physicality of engaging an opponent that is premised on the ability and conditioning of bodies and the technique that has been worked into them over many years. Winters’ body interrupted the assumed masculinity of sport and aggression, emphasising interaction over competition. This allowed for a moment where both performers flowed out of their floor hold and into lying on their backs, fist pumping tiredly in rhythm with the cheering, which accompanied the whole performance. After a few seconds they reengaged and returned to their sparring and teaming.

Both performers maintained a ‘game face’, their expressions telling us that they were concentrating on something outside of themselves that wasn’t necessarily each other or what the audience could actually see. Their movement, which required much strength and created many forms that were almost micro tableaux, ranged around the performance area, filling it. The absence of prescribed emotion heightened the impression that they had stakes in what their physicality was going to achieve in the moment, which, I suspect, led to the audience having an investment in the piece that was not based only in emotional receptivity, but in an abstraction of sport’s movements, techniques, and consequences, and of players’ and spectators’ bodies and relationships.

.

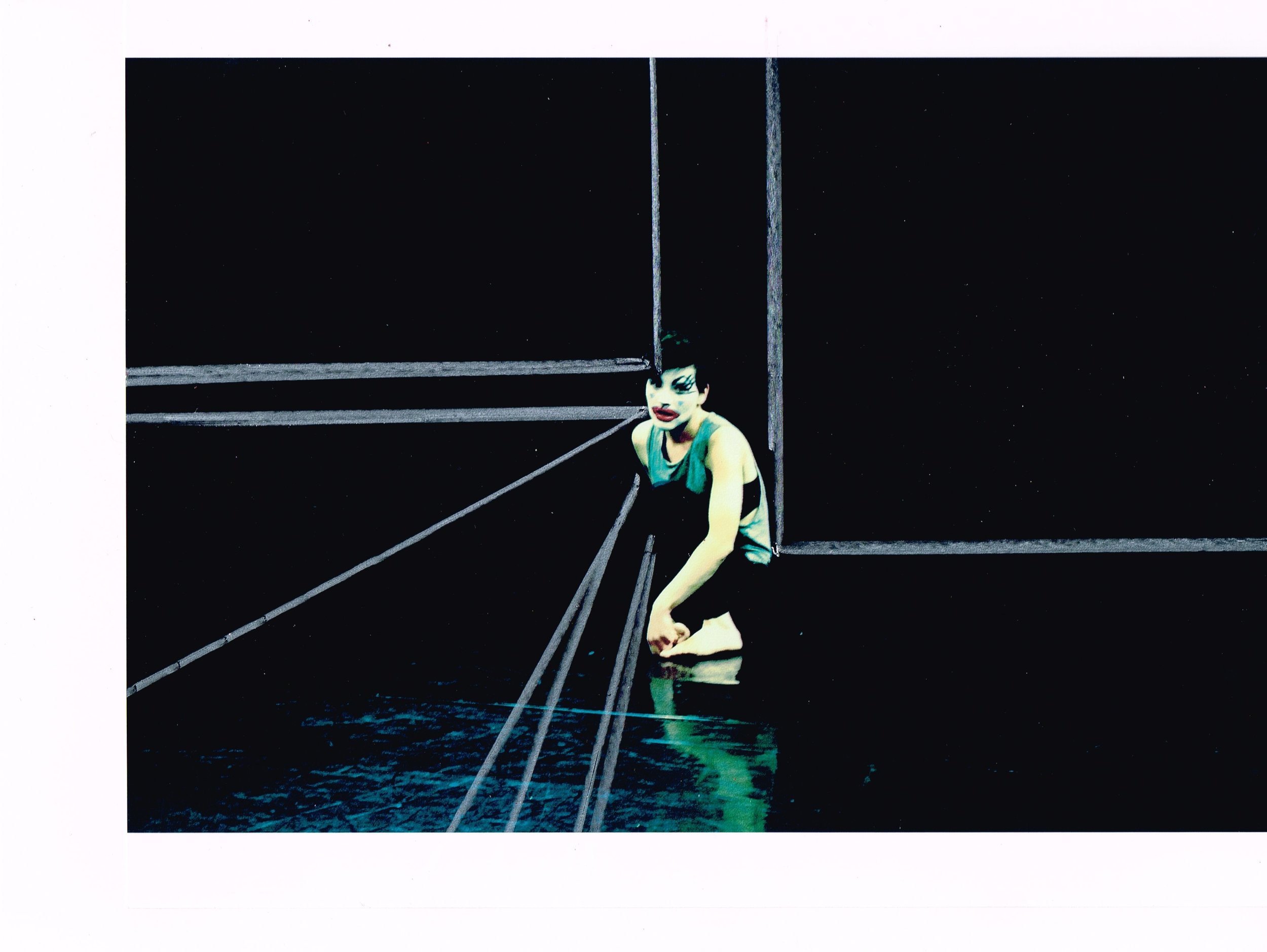

Kayla Jeanson, Brianna Ferguson, & Alexandra Winters

In Labyrinthinitis, Jeanson explores the effects of YouTube’s stabilisation tool on the bodies of the dancers she videoed. Learning the movements which would prompt the tool to act most noticeably, Jeanson created choreography that would elicit the greatest intervention by the tool. There is a resemblance between the successful gestures – swinging, swaying, eyes moving slowly from side to side, jumping, hands twisting and pirouetting – and it is tempting to think of them as a little primate-like or as the cause of the simultaneous movement of the background and floor line, but the piece cautions against such interpretation or categorisation, implying that this itself will change the way the work is seen.

Jeanson’s processed videos show bodies that we are watching via something else’s observation. The sensation of being behind some one’s or thing’s eyes is like playing a part in the movie Being John Malkovich but in this circumstance the observer, the Artificial Intelligence behind the stabilisation effect, changes in a real way that which is observed. Although popular consciousness is familiar with the principle that particles change according to whether they are or are not watched (the Zeno effect) and is parallel to research in the social sciences that posits perception can change how the perceived is interacted with, it is still shocking to see what those changes actually look like and how they effect us.

The jerks, the unnatural flow of the bodies whose natural timing has been disturbed, the odd panning in the shots, the slight zooms, and the shudders of the background, all make for an uncanny experience. These once freely moving human bodies, now processed, are assigned an A.I. interpretation of their movement and the bodies are corrected accordingly. Animation techniques are brought to mind, but this stabilisation effect is animating something that is already animated, that is living, in order to create what it calculates is conventional or ‘normal’. One could think of this as a kind of metaphor for the issues of body conventions much of the dance world struggles with. One is also reminded that defining and enforcing ‘the normal’ is a characteristic of tyranny. Thus digitising and editing bodies also raises questions of who or what does the defining and enforcing and what are the implications when we can no longer discern that an image or video is ‘off’ and therefore manipulated and hence what is real, what is not, what is true, what is a false, who is in control.

.

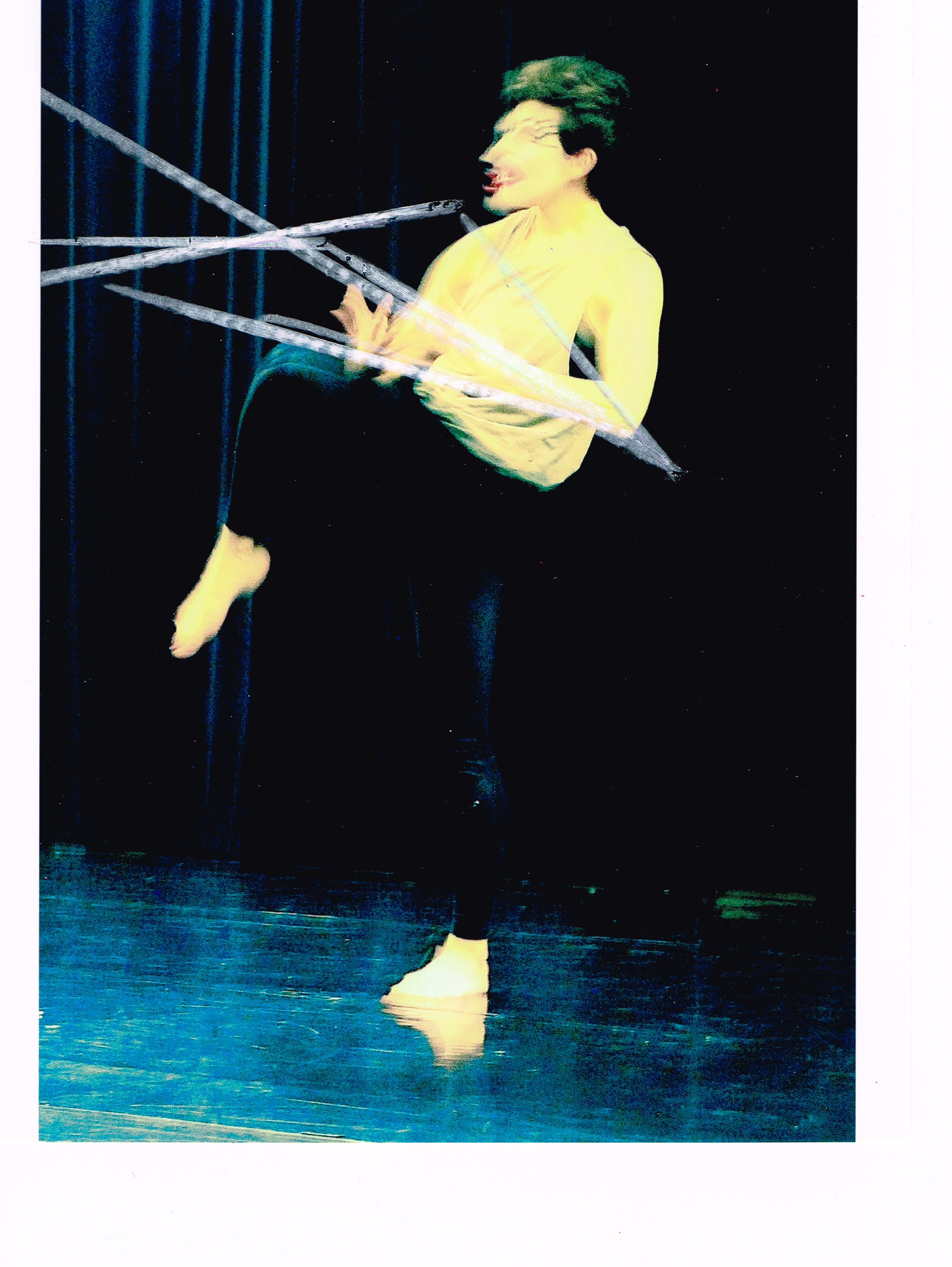

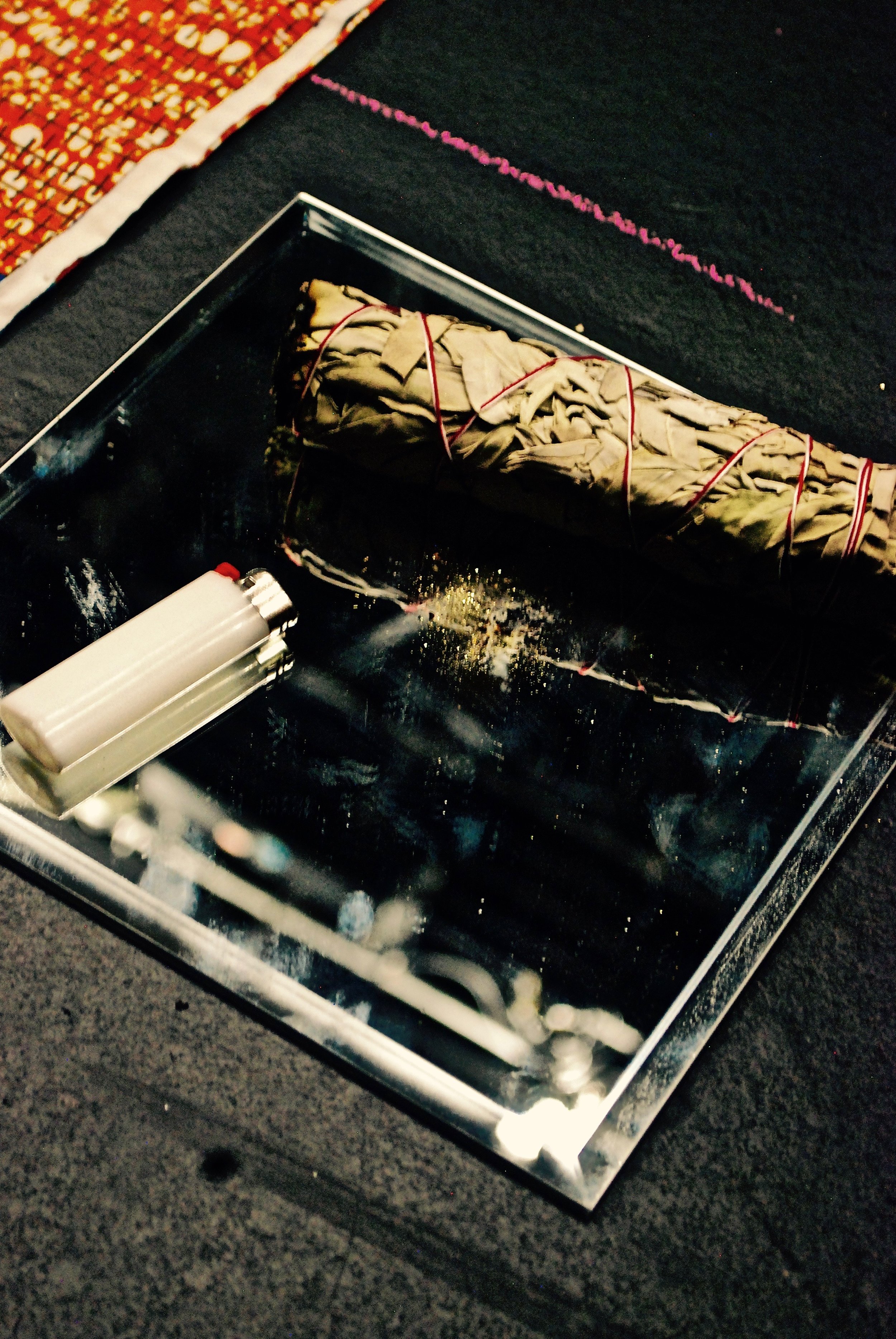

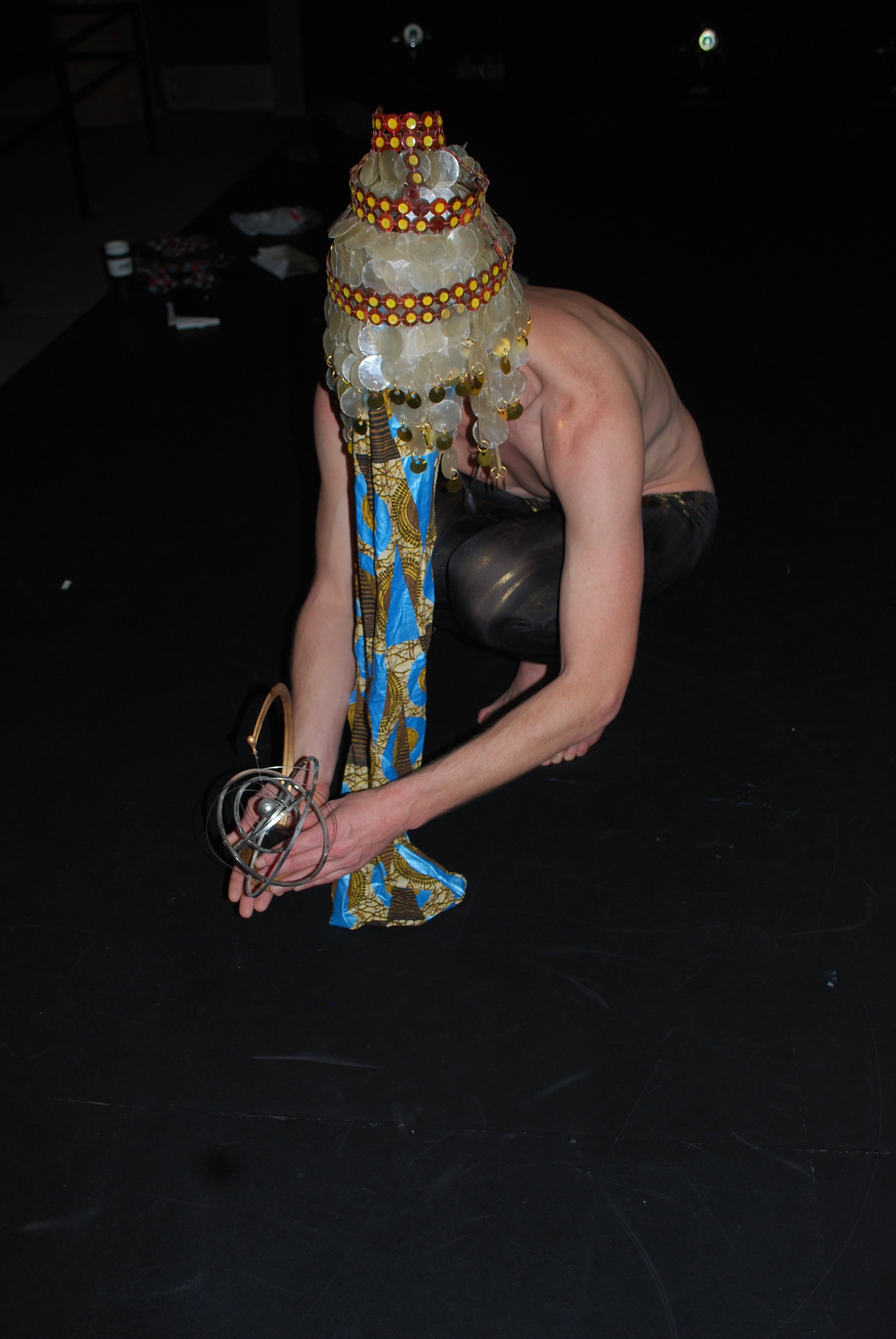

Davis Plett & Rachelle Bourget

Rituals are a means of encoding specific sequences of actions that are designed to exert a form of power. They often mark or are attempts at transformation. Bourget performed an intense interiority, her movement communicating a concentration and purpose usually reserved for ceremonies. She slowly crossed the space holding a cardboard box in front of her face and then after setting it down she removed a plastic bag from which in turn she took the dividers common to wine boxes then proceeded to slot them together to make three shapes we knew must be pre-determined given her manner of construction. This was part one and was, among several other things, a witty flirtation with the tedium that accompanies rituals with which we are overly familiar or have no stakes in. But the central preoccupation of the piece seemed more about deconstructing the power structures within bodies that have acquired particular vocabularies from specific training. Such training includes making itself clearly evident in the actions performed by those bodies, thus the bodies are allied to a set of rules created by schools of movement and thought. Plett choreographed the performance to objectify Bourget’s training which led to the disassembling of the meaning of everything she interacted with. The wine bottle dividers stopped being wine bottle dividers and became abstract sculptures; they were separated from their intended purpose (which named them) via a ritual. We still see the divider, and the training, but accept and believe the transformations and the opportunity to become immersed in the spaces that form when meaning expands.

In the second part of the performance, Plett in plain sight, puppeteers a crumpled, thin plastic sheet from the ceiling, fidgeting it’s four sides to make it become a ghostly jellyfish that descends onto an almost full Fanta bottle placed on top of a red sheet of Mylar over an overhead projector. Aside from the phantom/Fanta pun, the performance seemed a reinterpretation of Bourget’s ritual: whereas the first observed transformation was that of the cardboard dividers, the plastic bags in which they had been packed and then carefully folded away were also changed by her performance and were then able to leave the confines of their prescribed purpose to potentially flap away into another. Thus we see Plett’s training, as well as the ripple between accepting one story for another.

Playing Ball – Research series story

The waves tumbled over the rocks and onto the beach, muscular and doubtless. A friend of Kenneth’s, a pitcher, had told him how he’d go to the beach when he had the blues and imagine the sea was a cheering crowd willing him to do well. When this pitcher won a chunk of cash on a scratch card, he blew the lot on a couple of crates of baseballs. He took them to the beach and spent a day pitching them into the sea: an offering to the waters.

Kenneth had come into a little money himself and decided to do what his friend had done. He brought his two crates to the beach and as the sun was beginning to set, he pushed his hand into its well worn mitt and limbered up, swinging his arms, rotating his shoulders, twisting his torso, getting the joints lubricated and muscles warm. He’d spent more of his life playing baseball than not and his body was shaped by its rhythms and repetitions. A centre fielder and star batter, he had moulded his body to swing, sprint, catch, and throw with the greatest power and efficiency. The form suited him but he worried his mind had become conditioned into a certain shape too and that he wasn’t thinking and moving in the world with full autonomy.

He threw the first ball far out into the waves. The sound of the sea heightened his awareness of his own movement. Kenneth felt his concentration transform his physicality from utilitarian to ritualistic, a set of repeated gestures that allowed him to experience everything as everything. He was used to concentrating on his body but now it was as if the sea was washing a film away. He experienced himself with a fresh intensity, feeling the ball, his mitt, the breeze, the rising moon and his body as profoundly related to one another.

The moon was at its zenith when he abruptly stopped pitching. He realised he wasn’t exercising oneness at all, he was simply polluting the sea. “Shit,” he groaned, his arms dropping to his sides. He stared at the waves rolling on and on, their cheering sounding more like anger. Even his staring felt like it changed the sea – was that polluting it too? The rhythm of the water now seemed off, too jerky but also too smooth. He switched between staring hard and pretending not to look, trying to discern just what effect, if any, he was having. It made him nauseous and he tightly closed his eyes. In his head a bunch of ball players appeared, each looped on a snippet of their game movement. When he contemplated them as a group their movement was regular, recognisable but when he focused on one, her gesture wobbled and his own perspective rippled in response making him very uneasy. A disturbance in the shallows snapped his eyes open and his mitted hand shot into the air in reflex to the blob flying towards him at speed. He made the catch- a wet baseball. He scanned the waters expecting to see a swimmer but there was none. Taking a few steps forward to scrutinise the surf more closely he saw a dull glowing – a group of jellyfish bobbing like phantoms. Another ball broke the surface above them and Kenneth made the catch. Quickly he pulled off his mitt, grabbed his bat, and ground his back foot into the sand. He waited, bat raised, eyes on the shallows. Another ball hurtled towards him – he made contact – a fly ball. Another came, he made contact again, and the crack told him it was a homer. He watched it land far out into the moonlit waters. ‘What am I doing?’ he thought, throwing down his bat and shoving his mitt back on. He waited. Eventually a ball came, he caught it, and threw it into a crate. Another ball came and he passed it onto the crate again and a pattern began.

Dawn broke, misty and grey. Kenneth’s two crates were full and piled up next to them were enough balls to fill another two. It had been a while since the last ball had appeared but he was still alert and limber for a good while before accepting it was done. He straightened up and took off his mitt, an ancient piece of battered, memoried leather. He walked with it to the water’s edge and drew back his arm in preparation for a final, awesome throw. The jellyfish, with their strange staccatic ballooning, had gone. If he threw his mitt it would not be returned and even if it was it would be changed and no longer be a part of his body as it was now. He turned and threw it onto the top of the pile of balls. Somethings are simply yours.

______

hannah_g is a writer, contemporary storyteller, inter-disciplinary artist, mixtape DJ, and designer. She is interested in collectivity, place-making, and recollection.

She is also the Director of the Artist-Run Centre, aceartinc. and the editor of the gallery’s in-house annual publication, PaperWait. Here she co-founded Flux Gallery, the Cartae Open School, and the gallery’s first Indigenous Curatorial Residency.

She is available to write, perform, run workshops, mixtape DJ, and make things for you. hannah lives and works in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Treaty One Territory, Canada.

Essay

by Beth Schellenberg

2018 November – January Research Series

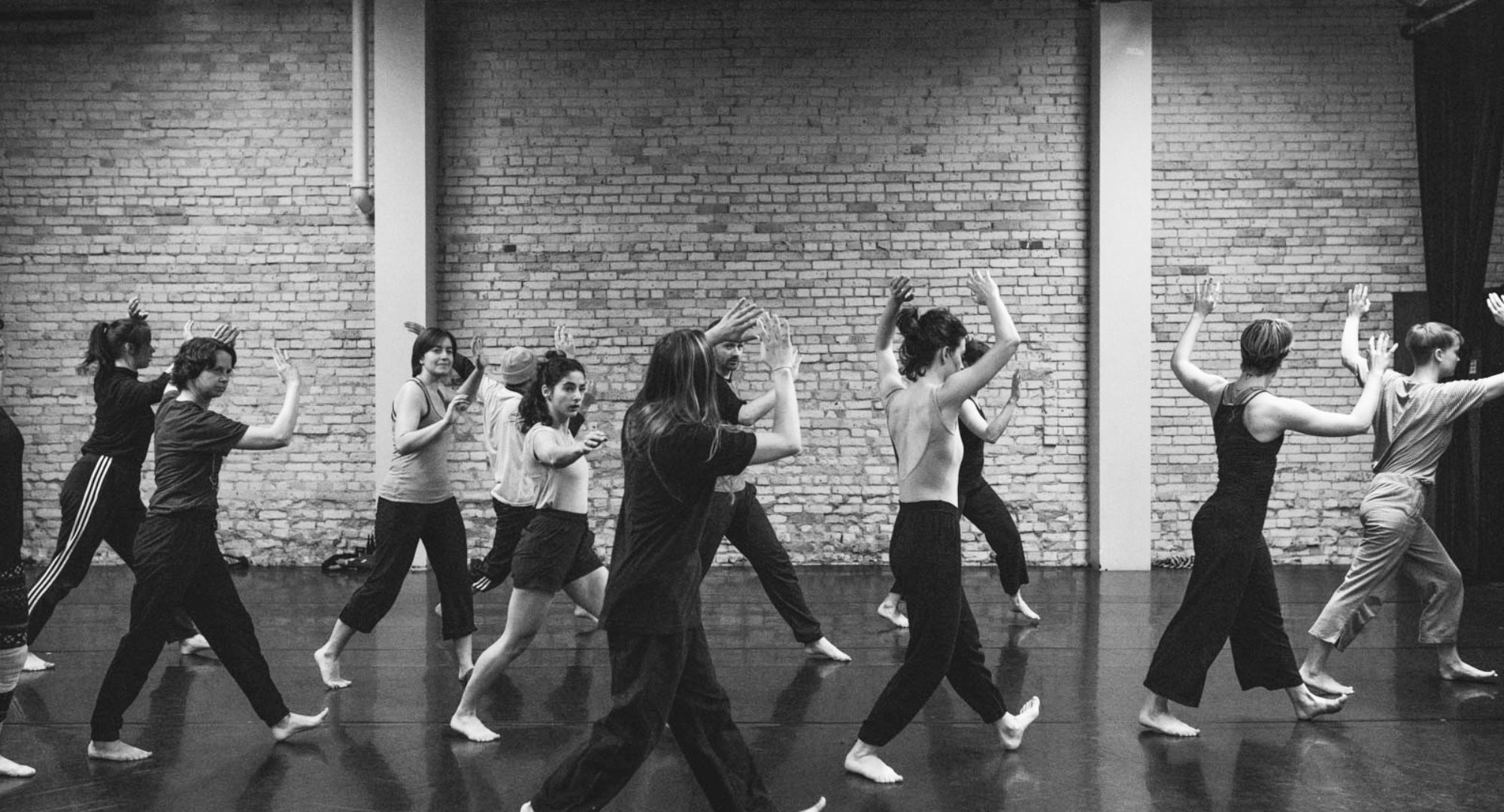

The morning I head to the Young Lungs studio is biting, the cold and sun making my eyes water. I am one of the last to arrive, and after removing a comical number of layers and setting my boots alongside the others, I enter the studio where researchers have already begun warming up. Two dancers in black athletic wear are being coached by a woman wearing lavender wool socks and a pink ponytail holder the same hue as her scarf. Another trio is across the room, squatting, shaking out limbs, humming and groaning. I recognize Alex, a local contemporary dancer, in a brown turtleneck and floral sweatpants, and Davis in black wearing glasses, I don’t recognize the third person, who is wearing royal blue and light grey, and has a head of tousled blond hair hanging around her shoulders. None of them look as sleepy as I feel, despite my early morning consumption of both coffee and green tea.

The last people arrive, introductions are made, and Brittney, the woman in blue and grey, Alex, and Davis begin with an interactive exercise they introduce as “fast sound and gesture”. The three stand in a circle and mimic each others actions, starting with facial expressions that evolve into sound and movement, growing bigger and louder with each passing minute. The result is disconcerting, and their groans, sometimes escalating into howls, are agonized, as though the sound is being pulled from deep within their bodies – with the sound goes their physical strength, leaving behind a quiet crumpled form. This exercise seems to last forever, and for the first of many times that morning I am taken by how willfully exposed these people are. There is often a vulnerability inherent in morning time, a state of being if not unguarded at least less guarded, but there is something about this intentional physical state, barefoot and illuminated by massive east facing windows, that is particularly striking.

After warm up the three set the stage for their improv performance, which involves a bathtub, a makeshift sound booth, and several lightbulbs hanging overhead. Alex and Brittany climb into the tub and face each other, while Davis takes a seat behind the mixer. Alex outstretches her hand to Brittany, who kisses it gently, like a lover or a mother, the gesture unbearably intimate. “I want you to come home” says Alex, plaintively, “I want you to come home” she repeats, while rocking Brittany like a child. Alex speaks of counting stars while waiting at night, and counting flakes of cereal when there are no stars. She ends saying “I am lost without you”, and the three switch places, with Alex doing sound and Davis and Brittany in the bathtub. This sequence verges into more bizarre territory but maintains the theme of loss, and of breakfast cereal. Brittany squats precariously on the edge of the tub, lamenting her compulsive consumption of cornflakes, the awful sensation of her teeth chewing cereal, yelling “it’s fucking disgusting, the cornflakes”. She finishes defeated, clutching her head in her hands and saying “the more I eat the more I hope maybe you’ll come home”. They switch again, and the session ends with Alex and Davis in the tub. Davis plays dentist, informing Alex that if she keeps eating cornflakes she’ll ruin her teeth, grind them down into dust, which he mimes by crushing a white pillow between his hands and the lip of the tub. He grabs the back of her head, shoves one of the hanging lightbulbs in her face and screams “say you’ll stop”, Alex, her neck craned and eyes wide, refuses. Davis says “my partner left me yesterday, that’s why all I have to eat is cornflakes, they always bought the groceries”, and slumps back in the tub. The improv snaps back and forth between hilarity and devastation, and is intimate, perhaps due in part to the domesticity the clawfoot tub elicits, but mostly because of the raw emotion spilling forth. The ways in which the prevalent themes of food, compulsive eating, and the fear of crumbling teeth, a textbook indication of anxiety, interact with each other is fascinating, but ultimately makes sense given how connected food is to home is to love is to loss is to anxiety is to food is to home and so on.

The woman in the pink scarf is Hannah, a dancer and choreographer, and her group is up next. After explaining that her piece is playing with ideas of instinctual movements and animal interactions, her dancers Sasha and Ilse begin. They make slow concentric circles by squatting low to the ground and swinging an extended leg, after several turns starting to move more rapidly, around and around, now faster and nearly frantic, approaching distress with ragged breath. After whirling, trapped in motion, for another few turns they collapse, fatigued. Sasha pulls herself into a seated position beside Ilse, who is lying rigid on the ground, observing her impassively for a moment, before lying down as big spoon, comforting her. In the next sequence they begin standing face to face, bodies nearly touching. Sasha is significantly taller but still they move as a many limbed creature, keeping space while maintaining close proximity, exploring the boundaries of bodies, of bond. After flinging their bodies far from each other as though they are opposing magnets, the piece comes to an end with both dancers curled on the floor. This investigation into interaction is not merely physical, it is also an emotional inquiry, an embodied relation that queries non-conscious impulses of empathetic and possibly abject connection.

We break for a few minutes to shift about on the floor, stretching stiffened limbs, before settling in for Jaz’ performance. In the meantime Jaz has been arranging two vessels about ten feet apart from each other, one a large cut glass punch bowl, the other a hand pinched clay bowl. They have also retrieved half a dozen water glasses and an aquamarine plastic pitcher from the studio kitchen. Jaz says that the piece is about ritual, walks over to the punch bowl, straightens their back, and picks up a glass, taking three careful paces before placing it back on the ground. They do this with the remaining glasses, painstakingly arranging them until a circle, roughly ten feet wide, has been formed. Jaz fills the pitcher, drops of water falling from their hand and catching light, the moment pregnant and over too soon as they take measured steps around the circle with the full pitcher. They fill each glass about two thirds, the sounds of pouring water punctuating silence. When all the glasses have been filled Jaz empties them, in the same measured way, into the clay vessel, which they play like a singing bowl, splashing water onto the ground, before lying prone on the floor. This ritual is mesmerizing, the immersive nature of the performance pointed back to a physical remembering, an inherited motion.

After the performances are done, the spilt water has been mopped up and people rearrange on the floor, we sit in a circle and I am confronted again by the vulnerability of this exercise. Perhaps it is commonplace for those in performance communities to witness such openness, but it strikes me that I am surrounded by people I barely know and they are brave enough to use their bodies to communicate ideas that are still in the process of being formed and articulated. This research series, bringing together people from different disciplines, points to a basic and perhaps incredibly reductionist thought: that everyone is seeking, albeit in different ways, to learn about themselves and each other. This is perhaps why it feels so intimate, so vulnerable. Not simply due to the morning, or the physical abandon, but because it is fragile and special to be able to witness strangers searching.

***

Dancer, choreographer, and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer’s psychotherapist once told her “feelings are facts”, a dictum after which she named her autobiography (Rainer), and one so simple as to be stunning. We are told to exist in a certain way, a way that is often based in someone else’s reality because it is more convenient, for society, for the individual, for both, rather than because it is what we are experiencing. These rules are often enforced based on how society perceives different bodies, and accordingly values, restricts, and/or denigrates them.

***

Sartre, famed father of french thought and misanthrope extraordinaire, is one of many philosophers who privileges control over emotions, and applauds striving to maintain mastery over oneself. In fact he seems to hate moments of vulnerability, speaking at length in Nausea about how repulsive humans are when they eat, and how disgusting he finds other peoples bodies. In a letter to a lover who expressed feeling an overwhelming sadness Sartre wrote “I hate and scorn those who, like you, indulge their brief hours of sadness. What disgusts me is the shameful little comedy rooted in a physical state of torpor” (Boulet 61). Sartre not only condemns this person for recognizing her emotional state, but also deems the physical manifestation of these emotions shameful. His vitriolic refutation of the importance of feeling, both physical and emotional, seems to reflect something of the privilege the patriarchy grants certain kinds of people.

***

I recall at various points in my life having my sadness levelled against me, being made to believe it was my fault rather than a product of how I was being treated. I remember how my body felt when I was sad. Times of pain and grief, fear and stasis can be physical, the body manifesting self-doubt in a stutter, tripping over curbs, allowing a glass tumbler to slip just so from a distracted hand. How to move with intention, let alone grace and fluidity, when the mind is reeling, one half using all of its strength to diminish the other? I spent much of my twenties being alternately weightless, about to slip up and away, and so heavy as to sink into the earth. I think I found my way back into myself by learning to un-believe what I had been told – there is power in unlearning.

During that nearly decade long period of general sadness or angst or depression or what-have-you I was told I needed to fight against and overcome, rather than explore, my feelings and intuitions in order to exist in reality. Whose reality? Certainly not mine, in fact this fight against myself took place in order to maintain relationships with people who were convinced their framework of ideals (or as Helene Cixous succinctly put it, their “conceptual orthopaedics” [10]) was a representation of a grand, overarching truth, when in fact it was a constructed ideology allowing them to act beyond the rules of what they disparaged as restrictive “social norms” while still benefiting from those “norms” and the hierarchy they create. This faux-political, airtight rationalizing allowed them to cause harm without culpability. For the most part these people weren’t intentionally malicious, but they were unwilling to engage with empathy and attempt to unlearn behaviour that served them at the expense of others. The troubling thing about my situation is that it is in no way unique, and that as a white passing, CIS woman who has a supportive family and network of friends it doesn’t begin to speak to the magnitude of repression faced by so many folks with less privilege than I. What is also troubling is that it echoes how our society at large functions.

Why did these people assume that I should live within their conception of the world, particularly when it was one that disenfranchised me? Is the answer simply the patriarchy? I suppose I could chalk it up to a “power” imbalance: the employer was paying my (minimum) wage, which meant I “owed” him and had to take whatever emotional abuse and sexual harassment he chose to inflict, or: the boyfriend said he “loved me more than anything (and more than anyone else ever would)” which somehow negated devastating betrayals, lies, and manipulations, and placed the onus on me to live with his destructive choices rather than on him to be better. Except this doesn’t feel like power to me, it feels like fear, like they were clutching to their conceptual orthopaedics with a death grip, white knuckled, terrified they would be caught out and lose their place in the world, or god forbid have to accept the validity of other people’s perspectives. Can this fear actually be a sign of hope? Can it be attributed to the fact that things are finally changing, albeit slowly, and that different bodies, minds, and ways of being are finally allowed to survive and thrive, that the white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy (™ bell hooks) we are so used to is finally being challenged?

***

Part of the problem: the enlightenment philosophies that inform our “western” conceptions of identity are built on binaries of mind/body, man/woman, human/animal, light/dark and tend to negate or at least ignore emotional and physical realities that exist beyond that of the privileged white male. Donna Haraway identifies such binaries as part of the “informatics of domination” that impede contemporary resistance to injustice (167). Theories of rationality, detachment, and mastery of oneself create a somewhat brutal meritocracy that demands if one has enough will and intellectual acuity they will ascend a mountain and become what they are (263 Nietzsche). Of course if one is born brown, black, female, impoverished, homosexual, etc. then society tells you what you are and how you are supposed to be, and it often isn’t an uber-mensch. Ultimately the doctrines of philosophies from early enlightenment to existentialist lack empathy, creating a very bleak outlook on human relations and difference.

A possible solution, or at least an alternative to the above: “affect theory”, which is defined as the study of “visceral forces beneath, alongside, or generally other than conscious knowing that can serve to drive us toward movement, thought, and ever-changing forms of relation” (Affect Theory Reader). These explorations acknowledge that bodies provide motivation, attachment, and desire, and strives toward a knowing that is not grounded in what we are told is real, but rather in dismantling those beliefs and focusing on what we feel could possibly exist. Anna Gibbs says that affect theory “might also take the form of an ‘anti-history’ or ‘counter-memory’ which attempts to detach the present from history as a constraining and defining identity so that it can be moved beyond and something other can be invented. This is an enterprise which, in charting the limits of the present, unsettles the taken for granted and suggests that things could be otherwise, leaving the future open” (6). This way of thinking provides a vital departure from enlightenment humanism and the various philosophies it informed, and engenders empathy, allowing more ways of knowing, conceptualizing and experiencing the world.

One of my favourite theorists at the moment is José Esteban Muñoz, who envisions ideas of a utopian, queer futurity through transgressive moments of aesthetic, performative culture. For Muñoz it is the moments taking place outside of, or between, the interconnected systems of domination that define contemporary reality and contain hope. In Cruel Optimism Lauren Berlant also focuses on themes of liminality with her theory of “the impasse” (21), which she defines as “a crucial place that lies between the old habituated life and something different, something that radically resensualizes the subject” (27). Her idea of a “refutation of the precious normative construction of domesticity and privacy [that] leads to an embodiment of the impasse” (Berlant 27) runs along the same lines as Muñoz’ assertion that we must reject the present social structure in order to “dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds” (1).

If we understand Sartre’s conception of freedom as a tortured knowledge of nothingness (Being and Nothingness) and Muñoz’ “ideality” of freedom to be a site of un-materialized, potential utopia which is predicated precisely on not-knowing, a stark contrast emerges, and at the risk of being reductionist I would guess that these differentiating ways of viewing the world, the non-verbal articulation of ideas versus the enlightenment definition of knowledge and thought, rather alter the ways people understand and perceive one another.

***

They way movement can elucidate ideas and feelings is remarkable, and illustrates how the body functions as a site of emotional and intellectual knowledge, containing information vital about ourselves but also information that is vital when trying to enact a social shift towards a softer, kinder world. Jaz’ ritual connects to a tradition of embodied articulation, and a turn back into oneself, and to the intrinsic knowledge we carry that can reveal previously unknown information. Brittney’s improv is an explosive example of release, the pent up everyday coming out as words and signs, as well as the intuitive bonds that can be forged by crossing disciplinary lines. Hannah portrays a physicality concerned with touch, and the manifestation of varying boundaries and connections we draw between each other, and perhaps within ourselves. These forms of research lie between what is consciously known and what runs beneath the surface, and are an identification of mutable, fluid ideas that can’t quite be pinned down, but whose contours can be traced. This kind of ephemeral performance is what Munoz envisions can literally save the world, and although I’m not as strident a utopian as he, there is a hope inherent in people striving to reach new spaces within themselves, with others, and with their bodies. Anna Gibbs perhaps says it best when she says that research can be “an experimental and productive forging of connections to new ends, rather than the analytical disassembling of a machine in order to show how it works, as if this (the analytic disassembling) were sufficient to bring about desirable change” (4).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berlant, Lauren Gail. Cruel Optimism. Durham : Duke University Press, 2011. Print.

Gibbs, Anna. “Writing as Method.” Affective Methodologies,

Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth. The Affect Theory Reader. Duke University Press, 2011.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in

the Late Twentieth Century.” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of

Nature, New York; Routledge, 1991,149-181.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. NYU Press, 2009.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, and Thomas Common. Thus Spake Zarathustra. Gordon Press, 1974.

Rainer, Yvonne. Feelings Are Facts: a Life. MIT Press, 2013.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness. Routledge, 2007

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Nausea. Penguin Books, 2007.

A Study in Migratory Bodies

A Written Workshop

by Jaz Papadopoulos

Pick something. Something you can do with your body. Something easy.

Something easy you can do with your body.

Something easy you can do with your body every day.

drink a glass of water say hi to yourself in the mirror look out the window and count to

ten do you favourite stretch for five breaths read one page of a book sign a song light a

candle light two candles light three candles light four candles and say your

grandparents’ names say your own name say all your names learn all your names so

that you can say them every day

For the first week (or so),

Your body will learn the thing.

You will remember to breathe while you’re doing it.

You will feel cool air in your nose and warm air on your lip and growing and shrinking

space inside your chest and back and stomach and diaphragm.

You will see your hands move or you will hear your weight pushing out of your feet.

You will learn where your floor creaks and where the dust in your home hides.

For the first week (or so),

Try to do the thing the same way every time.

You will wonder which hand you use

or which way you hold the glass

or which candle you light first.

You will notice patterns:

Where you focus your eyes,

and the rhythm of your breath.

If the floor creaks change, you can’t control it.

After the first week (or so — I’m no expert),

All of those first week noticings will become old hat.

They are easy now, and they just happen that way.

That same way.

Now you will notice new things.

What is the shape of your spine?

When you breathe, your shoulders move too.

You have so many more muscles than you realized.

You can slowly learn where they live and what they answer to.

Something easy you can do with your body every day.

It’s still not always easy.

Tape a piece of paper to the wall

and on the days you don’t want to do the thing,

write on the paper why not.

(Then, you will be free to do the thing.)

After some weeks (or so),

Think about:

- all the other times you did the thing

- all the other people who do the thing

- all the other people who have ever done the thing

Think of the thing like mycelium

All of the enactments of the thing that have ever happened anywhere on this earth over

millennia —

they can communicate.

Your thing secretly knows all those other things.

And,

secretly,

you do too.

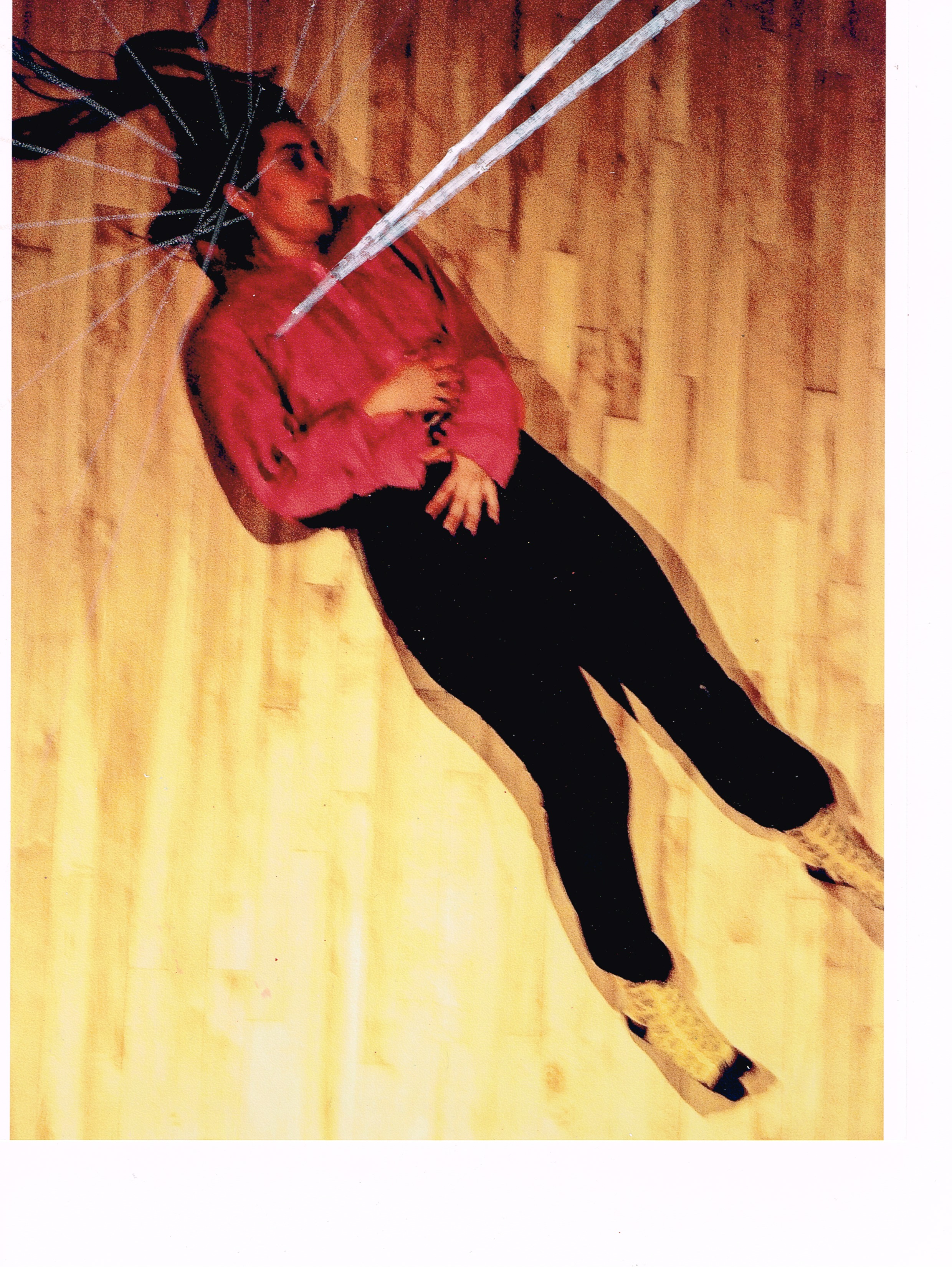

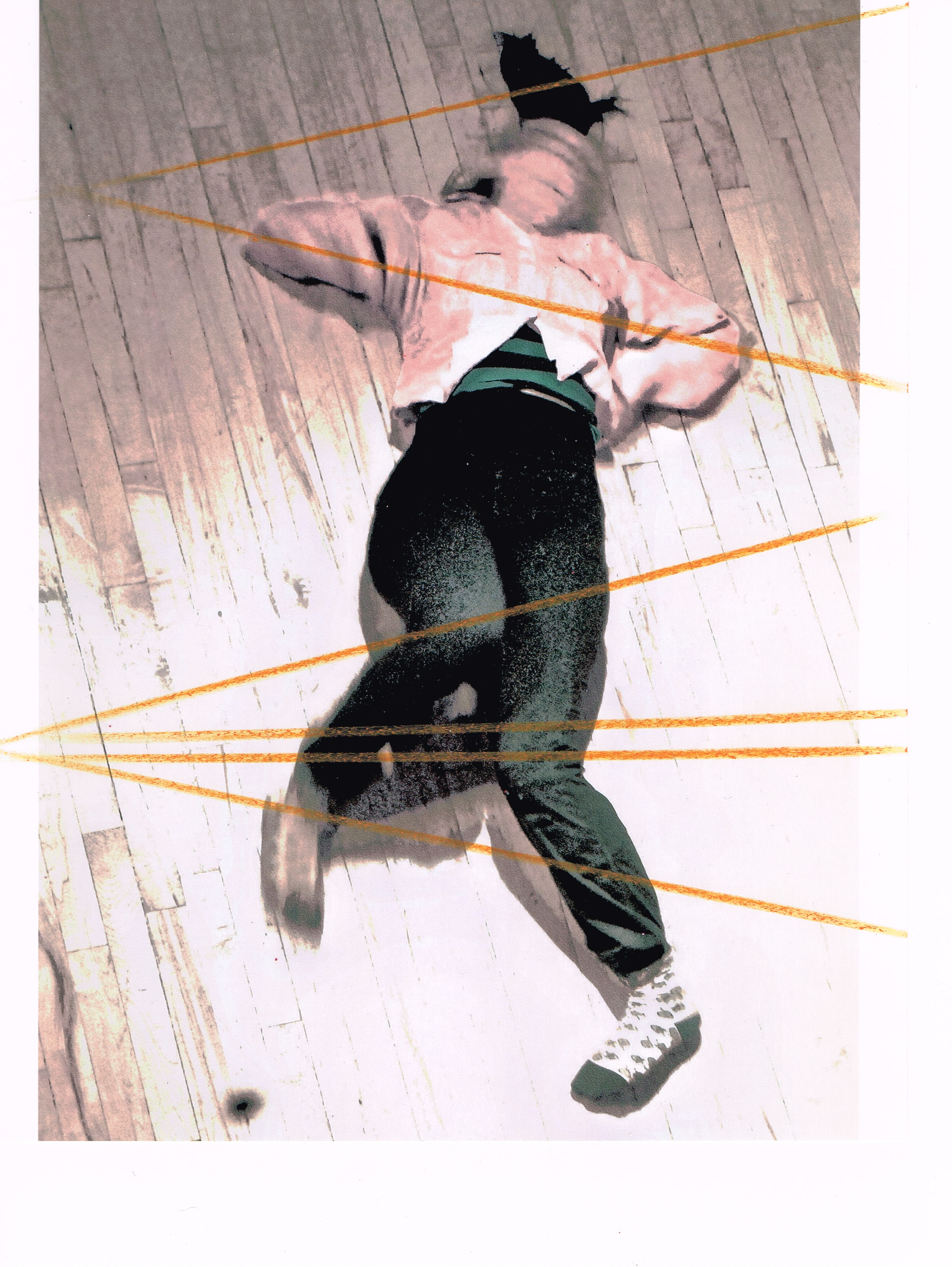

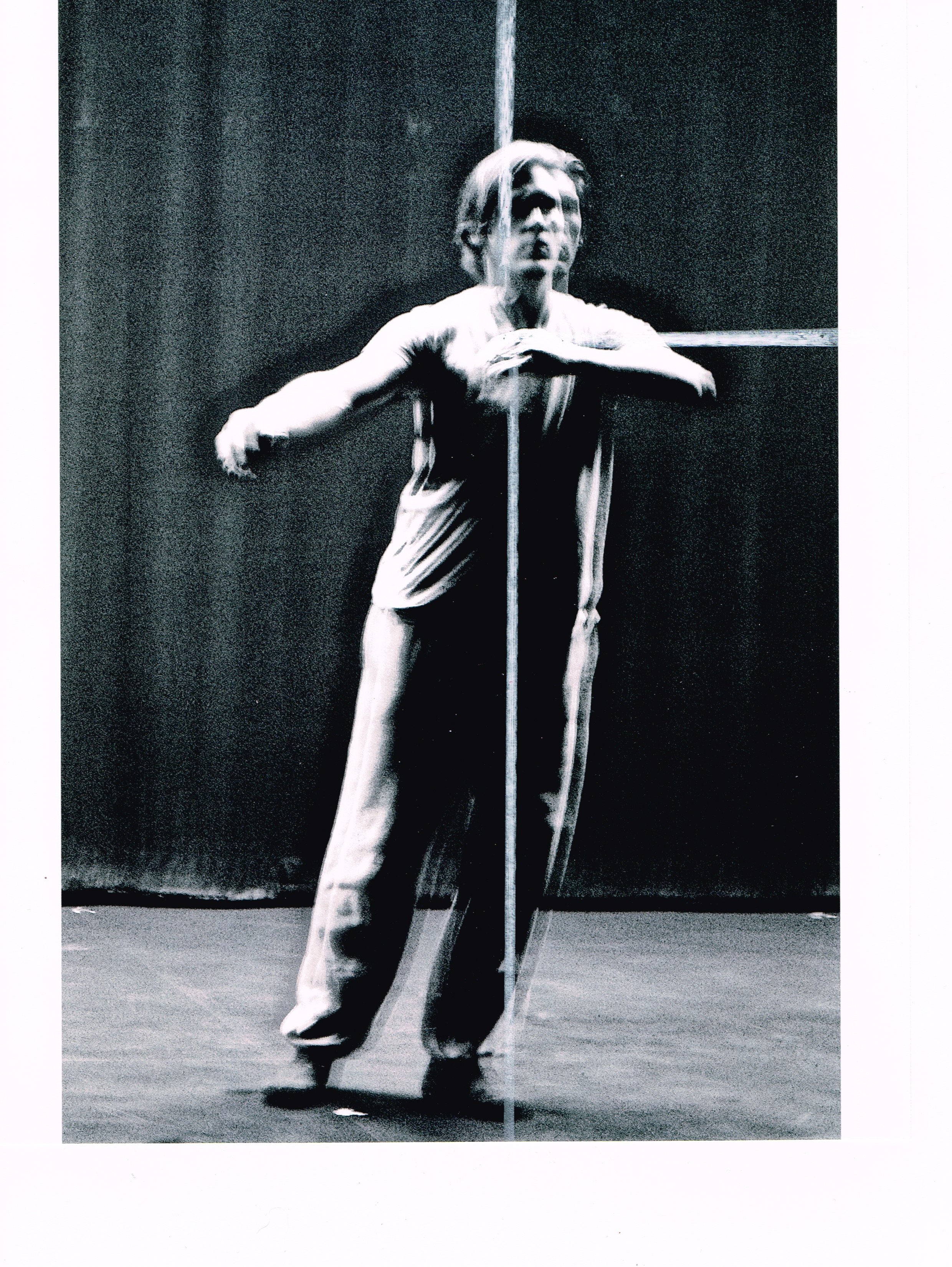

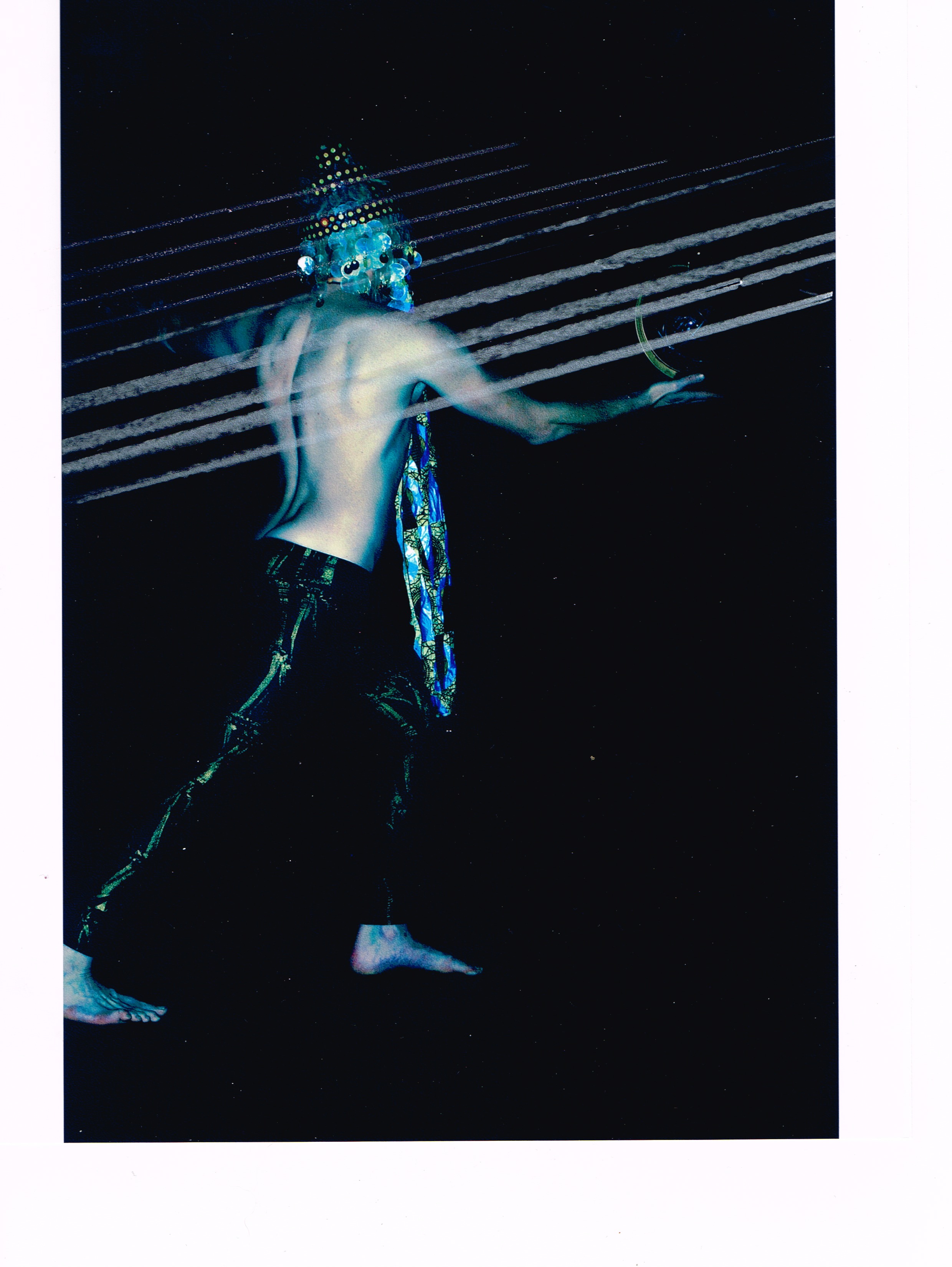

Visual Essay

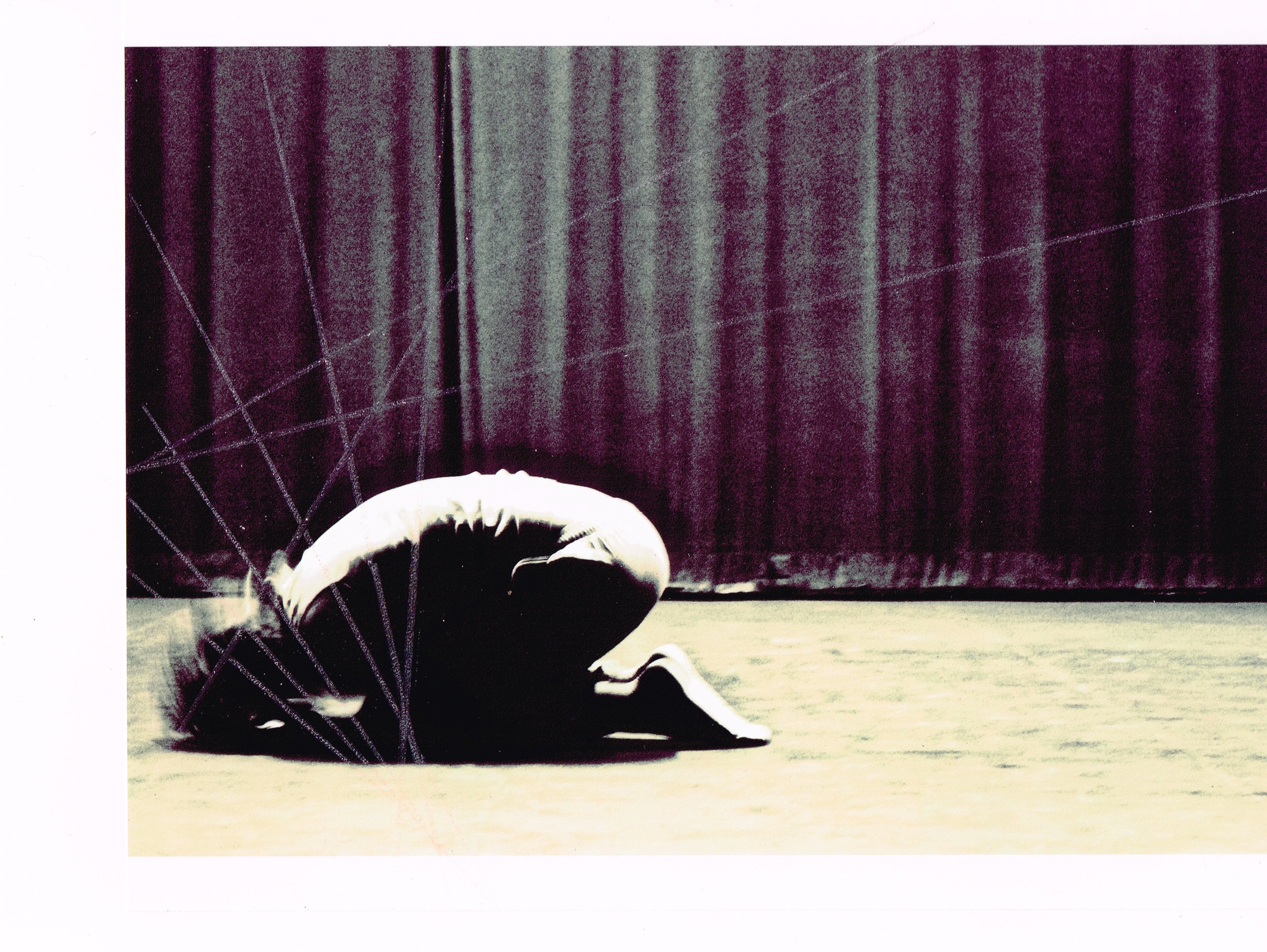

September – November 2017 Research Series Visual Essay

by Michelle Panting

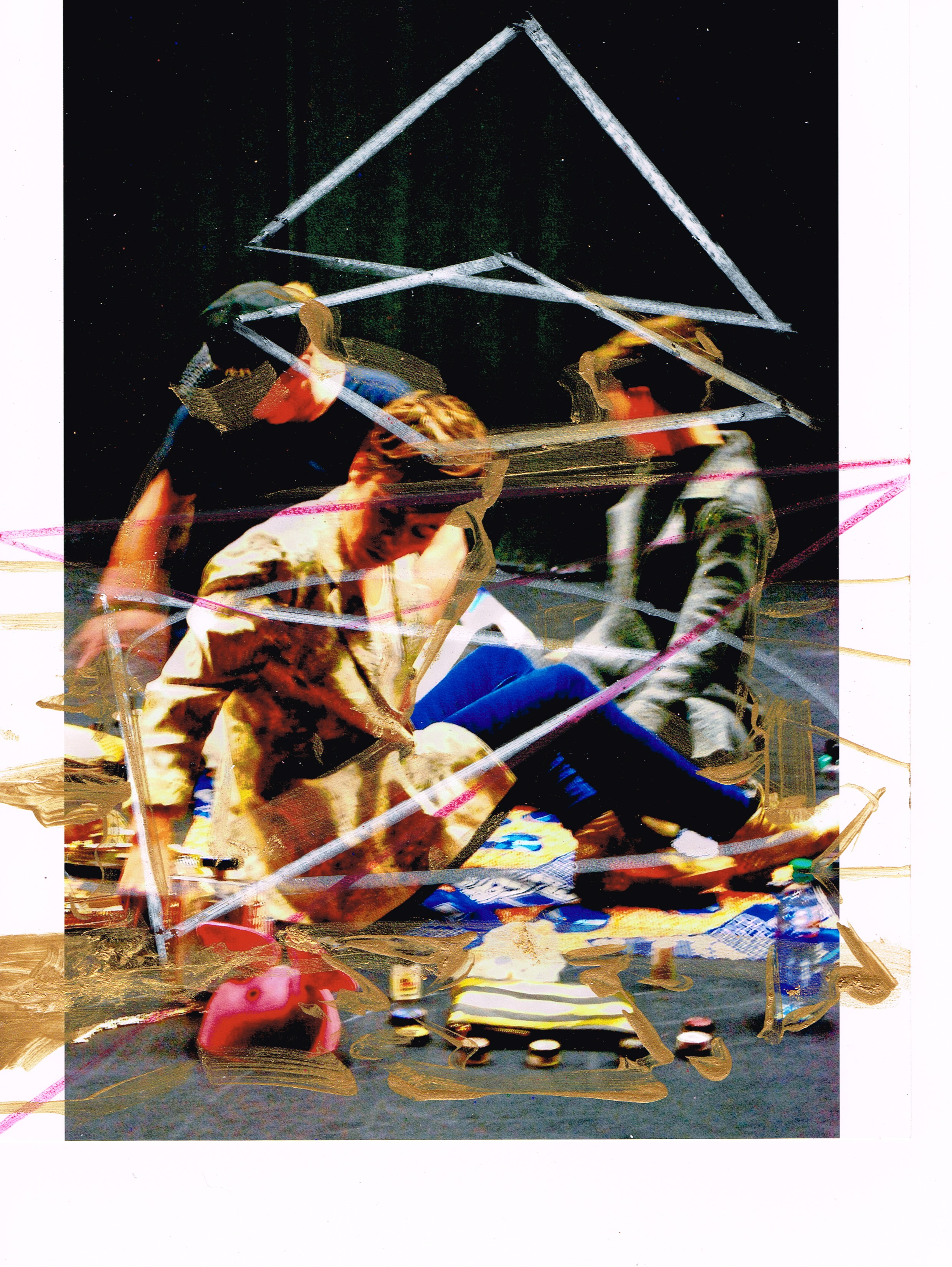

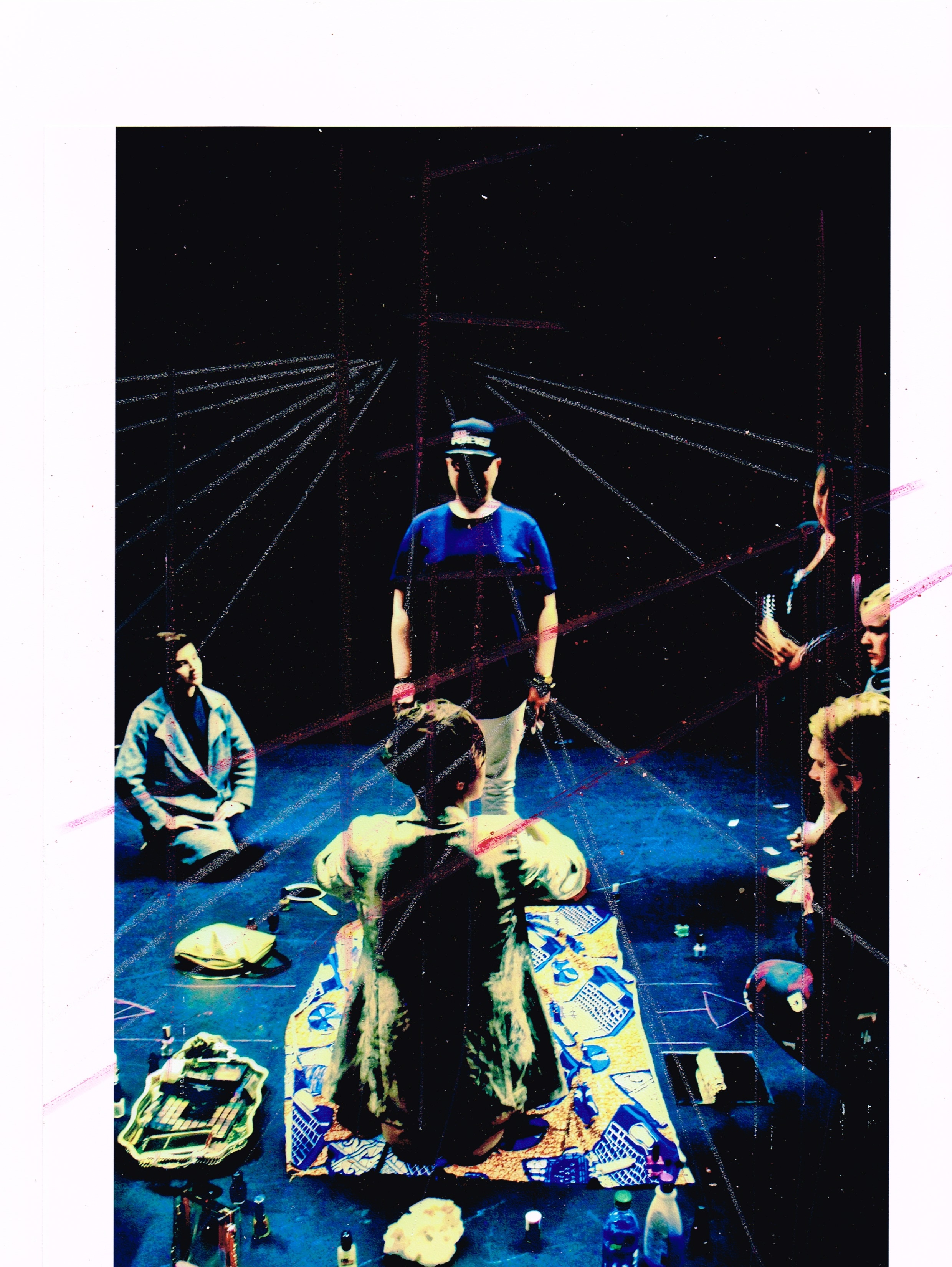

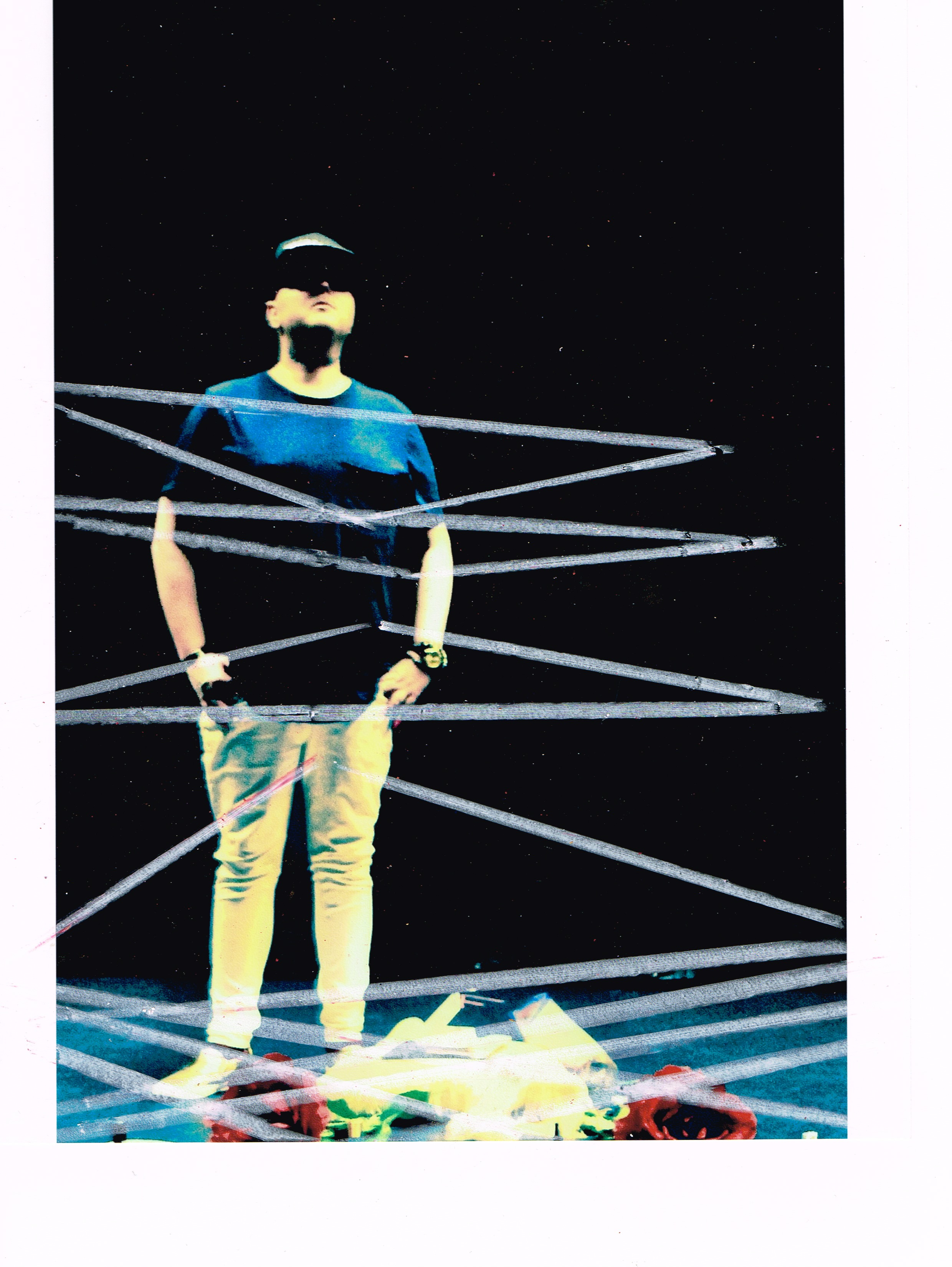

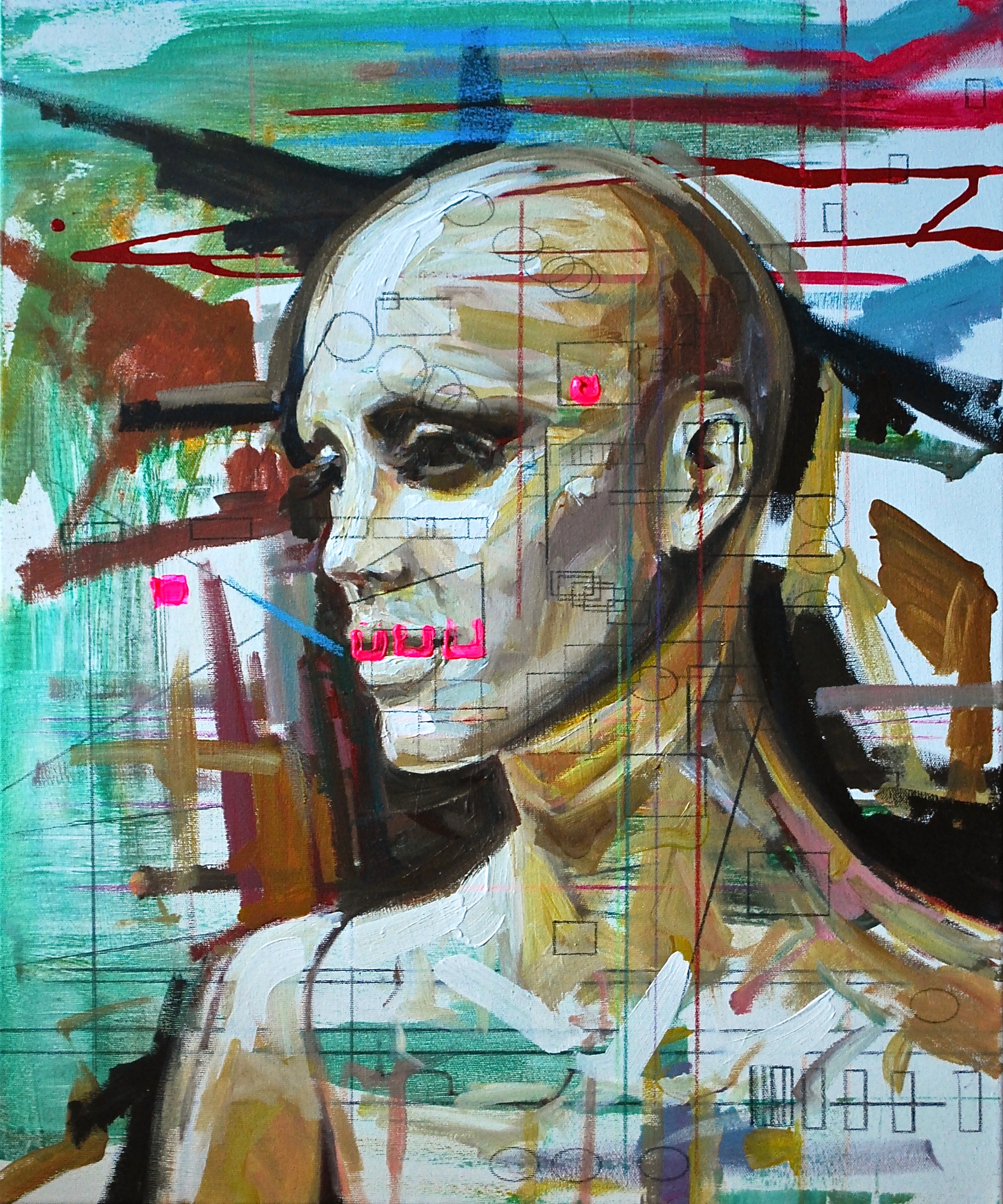

Davis Plett with Rachelle Bourget

Alex Winters with Warren McLelland

Kayla Jeanson with Alex Winters and Brianna Ray Ferguson

Self Portraits inspired by research

Michelle Panting is a writer and lens-based artist living in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In 2013, she

founded FULL, a website dedicated to documenting art, culture, and travel. Through FULL,

Michelle interviews artists and cultural influencers as well as capturing their work through

photographs. In her personal artistic practice, she uses both still and moving images to explore

issues of identity, mental health, and trauma. Michelle has exhibited her work at aceartinc. and

Parlour Coffee. She is currently enrolled in the Cartae Open School at aceartinc.

dance, discipline, and the anarchic body; or, how do i get my body to let me take a dance class?

2015-2016 Research Series

how do i get my body to let me take a dance class? this sounds like i’m invested in the mind/body split. I’m not, but i slide into it as readily as the next person born after René Descartes started thinking he is because he thinks he is. some believe that Descartes’s famous seventeenth-century statement, “i think, therefore i am,” founded modernity. right up to the present day, many people regard the mind or brain as the boss of the body. dualisms such as mind/body, man/woman, adult/child, good/evil all feature one term that is privileged over the other term. in the mind/body pairing, the mind is usually the one on top. a friend of ours is writing a play about cryonics. in cryonics, they sometimes freeze whole bodies, but you can also get someone to cut off your head and freeze it after you die so it can get reattached to another body when they’ve figured out how to fix what killed you. that’s how much some people value their bodies, apparently. in my case, though, when it comes to taking dance classes, anyway, it feels like it’s my body that’s calling the shots. it feels like i have an anarchic body, one that doesn’t want a leader or a mind thinking that it’s the boss.

anarchy means “no leader”: this is the literal translation from the Greek. i’ve been in a university environment for much of my life, so i’m used to leaders and to having my mind disciplined by them. for many years, i’ve had professors, advisors, employers, and department chairs telling me what to do. i might not like the hierarchical, top-down structure of so many of our school and work environments, but where the life of the mind is concerned, at any rate, being directed is something i can handle, even enjoy. and my body comes along for the ride.

disciplining my body, though, is a bit different. there are limits to what it’ll put up with. for years, i attended yoga classes, but, with yoga class, you don’t have to be all that disciplined: you can go or not go. it’s not like you have to be at a particular class on a regular basis. and because i have this somewhat hypermobile, disorderly body, yoga teachers would tell me to do the opposite of what they were telling everyone else to do or to do what felt right in my body. so i wasn’t exactly getting bossed around in yoga class. plus, half the time yoga instructors are making exactly the same shapes at the same time as everyone else so it feels like you’re all in it together. and moving to music at home or in a club or in free-style dance classes such as the Isadora Duncan workshop that Jolene Bailie arranged are experiences that i really enjoy. (Isadora freed dance from many of its restrictions, and i learned about her contributions when i was really young, so participating in this workshop was really wonderful thing for me!) no, it wasn’t these experiences that tested my limits; it was when i tried to learn a classical Indian style of dance named Kathak with Ian Mozdzen that my body rebelled.

the Kathak teachers were awesome, the people at the India School of Dance were super nice, and Kathak is super beautiful and interesting, but however much i thought i wanted to learn Kathak, my body just didn’t want to go to the same place at the same time every week and be taught to move with the kind of precision required by a classical dance form. having to move my arms or legs up or down or in or out several inches so as to mimic these ancient postures—however beautiful and charming these postures are—ended up being the proverbial straw, in terms of my physical training. Ian continued with Kathak lessons; in fact, he will be moving to India at the end of summer to learn more about classical Indian dance. and me? i dropped out. and i really wanted to learn Kathak, too.

the Hunger Games series of books and films features Twelve Districts filled with poor people who supply the citizens in the wealthy Capital with all that the well-to-do citizens need to thrive. it’s a lot like the relationship between the body and the mind of a scholarly type person: the body is like the Twelve Districts: it supplies the food and circulates the blood and the oxygen and then it has to just sit there and keep working at supplying the whole body with stuff while the mind—which resembles the wealthy citizens of the Capital—satiates itself with books and films and lectures. in the Hunger Games, because a Thirteenth District had tried to overthrow this unjust system sometime in the past, each of the twelve remaining districts has two of its young people selected to fight to the death in the annual hunger games while the citizens of the Capital get “entertained” by this blood sport. importantly, in each annual hunger game, there is only one winner. eventually, the people in the Twelve Districts rebel, inspired by the heroine, Katniss Everdeen, who refuses to kill all her opponents and become the sole winner of the games. trying to learn Kathak has taught me what i’d only suspected was true from all those years in yoga classes: that my body has a mind—many minds! entire districts!—of its own. perhaps a more egalitarian relationship among all these body-minds and my mind-mind (which no doubt has its own bodies, too) might make it possible for me to take a Kathak class sometime.

and this is precisely what anarchy is all about: egalitarian relationships. anarchy often gets a bad wrap. it’s frequently compared with chaos or nihilism, concepts which no doubt have their up sides, as well, although we seldom hear about them. in fact, Elise and Jasmine Allard, in their performance on January 16th, demonstrated that chaotic movement can be a safe and welcome expression of intense feeling if someone you love is there to catch you. i’ll talk about two separate moments from this performance: in the first, Jasmine holds Elise around the waist while Elise moves her arms and legs intensely; in this first instance, intense movement is enabled by Jasmine’s grasp. in the second of these two moments, Jasmine dances around like crazy until Elise can’t stand it any more and stops her. each sister is the ground that supports the other’s wildness. love both enables and disables chaotic movement.

researching this paper, i learned that contemporary theorists of anarchy embrace wildness and that they are concerned about oppression and the abuses of authority. authority tries to convince us that the few are more forceful than the many. no one in their right mind,—or maybe i should say “in their right body”! or, “in their right body-mind”!—would believe this for long, would they? Isabell Lorey is one of the scholars who is currently theorizing anarchy. Lorey writes about the 2011 Occupy Movement, the writings of philosopher Jacques Ranciére, and the idea that real democracy—by which Lorey means direct democracy, as opposed to representative democracy—is anarchic. what Lorey wants us to do is to practice democracy, real, anarchic democracy, all the time. she calls this “presentist democracy” (59). fill all of our presents, all of our nows, with real, egalitarian democracy, that’s what Lorey advises. And, if democracy is what we actually want, this recommendation makes a lot of sense, for, as literary theorist Jon Clay puts it, “the equality of beings is not imposed … [on us] from ‘above’ … but is rather … [our] own”; it “is assumed among … [ourselves]” (15).

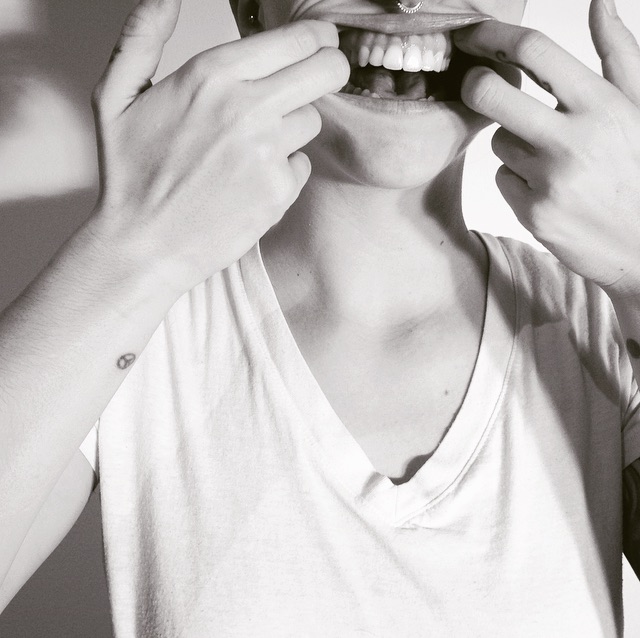

image: Sasha Amaya

Lorey’s recommendation about being present involves having a different kind of relationship with the past and the future, a relationship that is perhaps more distanced, or more occasional. instead of thinking about the past or the future a lot, might we choose, instead, to think about them only when we really need to. rather than “intending” to do a given thing, might we “carry” an idea “with us,” instead? would this be a substantially different way of doing things? how do we “get out of” dwelling in our pasts or in our futures? i think that Brenda McLean and Brittany Thiessen demonstrated a way to do this in a sequence of movements accompanying an apology. during their rehearsal of “Dinner,” a vignette from Caryl Churchill’s Love and Information, Brenda flippantly, insincerely apologizes to Brittany before following this up with a sincere, heartfelt apology. during the flippant apology, Brenda turns her back on Brittany and moves away from her. but during the sincere apology, Brenda wraps her entire body around Brittany, who is seated on the floor. apologizing addresses feelings of guilt, grief, or regret about an event that happened in the past. an insincere apology will keep this past event in play and maintain the distancing effects of estrangement. in contrast, a sincere apology can collapse this distance, assuage troubling emotions, and bring people together in the intimacy of a present moment of reconciliation. and Brenda’s and Brittany’s movements demonstrate how collapsing space collapses time, too. the direction and orientation of their bodies in space encode the temporal dynamics of the sincere and the insincere apology and bring to life the presentist politics recommended by Lorey .

these days politics has been largely reduced to policing people who are barely able to eke out a living (91). this perspective about contemporary politics is associated with thinkers such as Giorgio Agamben and Michel Foucault and it is a perspective that is also shared by a theorist named Mick Smith. while writing about how we might stop dominating what he calls “the more-than-human world,” Smith celebrates wildness. he calls wildness innocent, “ethically anarchic” (92), and “synonymous with creative freedom from social restraint” (94). Smith’s “more-than-human world” played a significant role in classes offered during the Young Lungs Research Series. on January 24th, facilitators Ali Robson, Janelle Hacault, and Sasha Amaya asked those who attended the classes to become sand, water, gulls, and trees! French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari see all earthlings as interconnected, as assemblages that are always becoming with the things that they—we!—come into contact with. this is true in the most basic and fundamental way. when we eat mushrooms, melons, or mango, we become these plants and they, in turn, become human beings. our interactions makes us assemblages of human and non-human parts. we breathe in what trees exhale—and vice versa! other kinds of becomings took place during these classes, as well. Sasha asked class participants to move around the dance floor with different body parts doing the leading—first the pelvis, then the ribs and the feet—people were even asked to let their bodies be led by more than one body part at once! in becoming-led by pelvis-minds, rib-minds, and feet-minds the leadership of the thinking head was disrupted, although it, too, was given its chance to take the lead! on another occasion, in a rehearsal exercise featuring one person mimicking another person’s everyday gestures, dancers Freya Olafson and Lise McMillan were asked by creator Treasure Waddell to become one another!

these types of exercise ask us to engage in a certain wildness, or in what Mick Smith calls “creative freedom from social restraint.” in this phrase, Smith celebrates freedom along with wildness. i would sure love to celebrate both of these ideas, too. but while celebrating wildness has many fans among anarchists, there are some thinkers, though, who argue, and very convincingly, too, that the concept of freedom is just another tool in the massive toolbox of those who police us. in fact, a theorist by the name of Nikolas Rose argues that governments invented freedom! as Rose explains it, governments convince us that certain behaviours are reasonable and normal. then governments convince us that we freely choose these very behaviours that they have conditioned us to adopt! Rose suggests that we think the way our governments want us to think, including and perhaps especially when we think that we are free. and thinking that we are free when, in fact, we are being highly disciplined and rigidly policed by those who govern us may be one of the biggest problems, in Rose’s point of view, that we moderns face.

Seeing Rachelle Bourget in rehearsal really brought home to me the visual dominance of the thinking head and its companion, the expressive face. for the first part of the rehearsal, i’m sure i spent as much time looking at Rachelle’s face and head as i did observing her dancing body. and even as i write this i realize: there i go, participating in the mind/body split again! i’ll start over. at first, i spent as much time watching the top eighth of Rachelle’s physical form in rehearsal as i did watching the other seven-eighths. then Rachelle wrapped a red scarf over her head and almost everything about my viewing of her movement changed. Rachelle’s head became another part of her moving body, an eighth of her body as opposed to the head of a body. lots of other interesting things became apparent, too: many of her movements were directed sideways; in other words, they were oriented towards the horizontal plane. (poststructural theorists, much like anarchists, are very interested in collapsing hierarchies, and they talk a lot about collapsing them by putting things side-by-side. poststructuralists are all about the horizontal, the lateral, the sideways.) to return to Rachelle’s dance: with her head covered, Rachelle’s limbs—pale in contrast with her black clothing and red scarf—came more into focus and the way she moved one arm as if to fit her elbow into the curve of her waist came to seem like an exercise in self-construction, something i might not have noticed had Rachelle not donned the mask. at the same time, Rachelle’s other arm was angled such that the space between this second arm and her core became a hole that drew my attention to the air within which she moved, air that was shared by everyone else in the place. also, Rachelle’s body made curves where one would not expect them and straight lines where i would never have thought them possible; for instance, at one time, Rachelle’s arm and shoulder were angled in such a way as to point straight down at the floor while the rest of her figure remained erect. i’ve put a slide of the “Russian feminist punk rock protest” (wiki) group Pussy Riot up on the screen because the effect of Rachelle’s dance, on me, anyway, was very political in a horizontal, egalitarian way. the other seven-eighths of our bodies offers so much!

in the introduction to his book Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement, André Lepecki explains that, “Rethinking … [what it means to be human] in terms of the body is precisely the task of [dance] choreography” (5). Lepecki has his criticisms of choreography, however, due to the “commanding voices” of its masters and the extensive discipline it requires of dancers who must nonetheless maintain a posture—and the imposture—of spontaneity (9). Lepecki goes on to talk about how dance is supposed to be all about movement. movement is the ontology or beingness of dance, as, since the Renaissance, at any rate, dance has been understood to be the art form that is all about uninterrupted, unceasing, rhythmic, flowing, movement. modernity, itself—that is to say, the period that stretches from the time of Descartes’s famous statement, “i think therefore i am,” all the way up to the present day—, is said to be all about movement, too, by some theorists; and Lepecki agrees.

but Lepecki is something of a rebel, as well. while he agrees with those who argue that modernity is all about movement and that dance, since the Renaissance, has been all about movement, he rebels against the idea that dance needs to be defined this way, preferring, instead, an expanded definition. Lepecki would have dance appreciated as a dynamic political force that embraces the body’s movement and its stillness, as well as the contributions of the philosophical, theorizing mind. now, what Lepecki says about dance being an art form that is predominantly about movement makes a lot of sense. i wonder, though, about his suggestion that movement is, as he puts it, “the kinetic project of modernity” (my emphasis 3). another way to look at it would be to think of modernity as being about people coming to terms with the fact that everything is always already in motion as well as the fact that the earth isn’t some still point at the centre of the universe, the way many Europeans apparently thought it was before Copernicus. dance, making use of both movement (and relative stillness), may be the art form that can help us the most as we come to terms with the fact that movement and change are the only constants, the only things that don’t change.

Mark Franko is another theorist who is interested in dance’s political contributions. for Franko, dance need not be the traditional, choreographic product of a student who mimics a teacher; it can also be the incorporation or becoming-embodied of the gift of dance. he makes this claim in “Given Moment: Dance and the Event,”a meditation about how dance, post 9/11, can help us come to term with events, especially traumatic events. Franko foregrounds the teaching methods of a Balinese dancer and teacher named Mario who transmits dance moves with his own body by “position[ing] himself behind his pupil whose arms and torso he manipulates into positions” (119). as one pupil puts it, the person being taught is like a tree whose branches are being arranged. Since the dance moves are not being “transmitted across a mediating space of observation and interpretation” (120), Franko characterizes this kind of teaching as a gift. this teaching is the giving of “self-force”; it is “the communication of dance as gift” (120).

The Young Lungs Dance Exchange Research Series has foregrounded the gift of dance and genuine spontaneity, too, particularly in the form of improvisation and collaboration. during her show, Treasure Waddell used improvisation to include the audience in the collaboration. the Research Series was itself an extensive network of collaboration. in fact, i wonder if the degree of collaboration during this Young Lungs Research Series might even address a criticism that some theorists make about gift economies. some theorists suggest gift-giving necessarily creates debt. if you give, there is the expectation that the person you give to will give something back, which is the debt part. in the Young Lungs Series, the creator of one show was a dancer in another and a dancer was also an administrator and on and on! so, in a situation with this degree of collaboration, where people are giving and getting all the time, finding someone who could be experiencing a lack of a reciprocity that could be called debt might actually be quite difficult! there is no doubt in my mind-body district that there were masters of dance involved in the processes of these past months, but the degree of reciprocity among the participants has made hierarchy virtually indiscernible.

collaboration may be another way to think about anarchy. if we (and our body parts) are always taking turns leading the way, are there still people whom we might characterize, in total, as leaders?

theorists of anarchy are frequently theorists of utopia, as well. and, like the word anarchy, the word utopia uses negation to make meaning. whereas anarchy means “no leader,” utopia means “no place.” put another way, the word utopia suggests that there is, in actuality, no fabulously wonderful place, no place in which we all might want to be and become together. but maybe, if we were to practice the kind of presentist democracy that Lorey recommends and if we were to have a revolving leadership such as the one demonstrated in this Research Series, we could have anarchy in both senses—in the dual sense of direct democracy and in the sense that there is no one person who is “the leader”—and maybe we could have utopia, too, here, in this place where we live. which would mean we’d need to coin a new word, a word for utopia achieved. how about the Cree word “ōmatowihk,” which means “in this place”? we could say—here’s a sample sentence—the Young Lungs style of dancing and dance-making is “ōmatowihk,” or the state-formerly-known-as-utopia achieved “in this place.”

oh, and i think i’ve learned a way to get my body to let me take a dance class! maybe i need to stop disciplining my mind quite so much; maybe this way my body can handle a little more discipline!

Co-founder Natasha Torres-Garner introduces a. charlie peters.

Works Cited and Referenced

Franko, Mark. “Given Movement: Dance and the Event.” Of the Presence of the Body: Essays on Dance and Performance Theory. Ed. André Lepecki. Middeltown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2004. Print.

Lepecki, André. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. New York: Rutledge, 2006. University of Winnipeg eBook. 21 Nov. 2014.

Lorey, Isabell. “The 2011 Occupy Movements: Ranciére and the Crisis of Democracy.” Trans. Aileen

Derieg. Theory Culture and Society 31.7/8 (2014): 43-65. SAGE. Web. 22 December 2015, Rose, Nikolas. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1999. Print.

Smith, Mick. “Primitivism: Anarchy, Politics, and the State of Nature.” Against Ecological Soveriegnty: Ethics, Biopolitics, and Saving the Natural World.

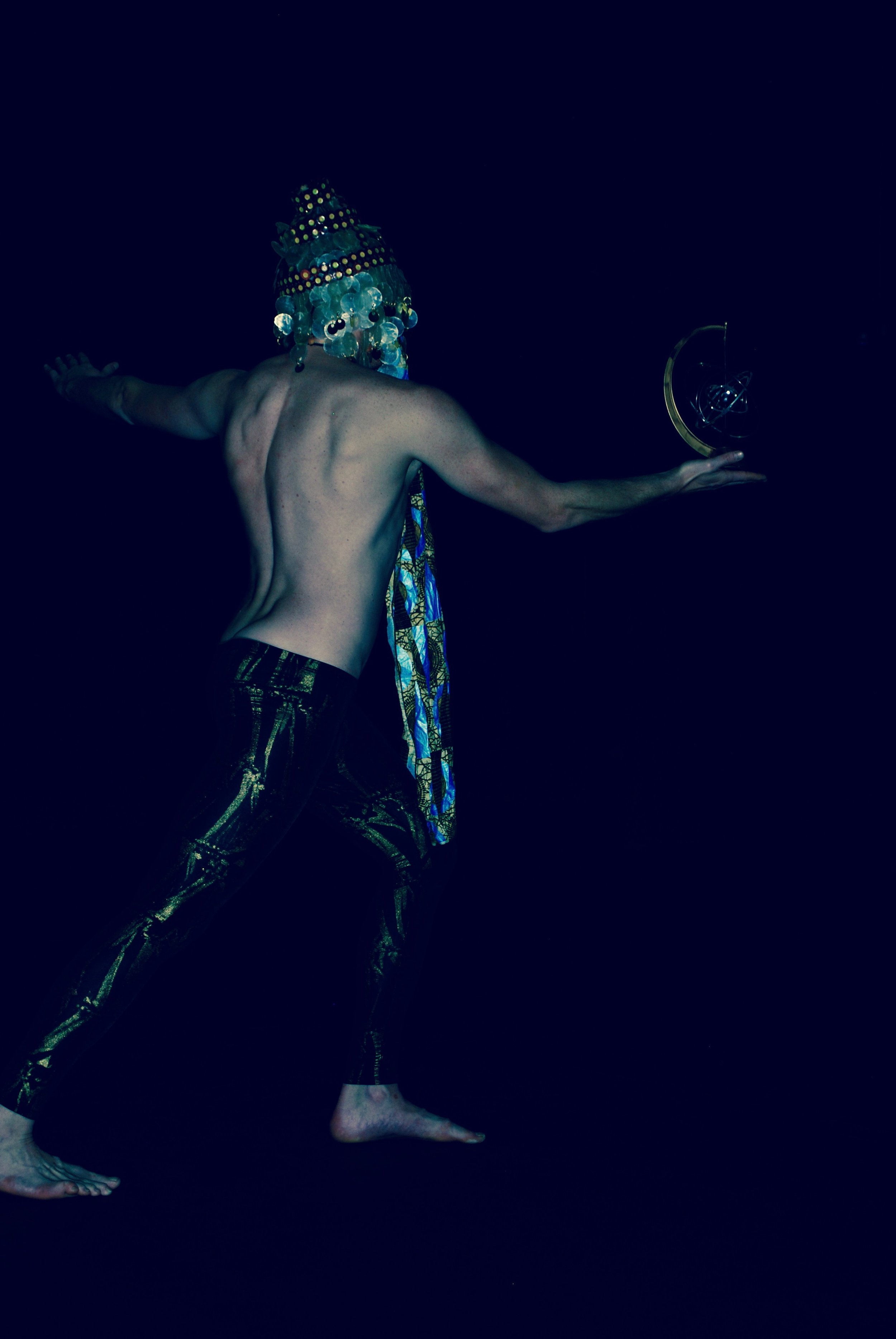

In Flux – A Visual Essay

The Ritual ~ Climb ~ The Performance ~ Velvet War

Still ~ In Flux ~ Mercury ~ Robot Empire ~ Heavenly Bodies ~ Ghost

Rehearsal/Research

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

It’s a Big Mess: Non|Sense Making on a Damaged Planet

By Praba Pilar

I dedicate this talk to Glamdrew Andrew Henderson. I am honored to have been a part of his process with Eroca Nicols and collaborators Carly Boyce and Mars Gradiva. I am grateful he took my secret to the grave.

Life, vida, biome, biotic, creation – always a process, never a state. Whether its biopoiesis, abiogenesis, or that great big bang, maybe its terrestrial, extraterrestrial, artificial, augmented, extended, simulated, telepresenced, ectropic or extropic – we don’t REALLY know if it comes from intergalactic primordial gas or just plain subatomic play. Which brings me back down to Earth.

What is life as we enter the 6th extinction? Can we stay with the trouble?

Can we confront the necrosis at the core of our contemporary CULT OF THE TECHNO-LOGIC? Can we crawl away from the cult of necrotic egocentrism oozing over the world in globalized neoliberal capitalist crapdom?

I am a twinned larvae, segmented by distributed intelligence into rejecting the egocentric unitary self-recruitment of the failed human project. Naming the homo sapien as the human ignores our microbiome, our 90% of our DNA that is not human. [LARVAL SCREAM] In the segmented paramythology of LARVAL ROCK STARS, my twin Anuj Vaidya and I find many historical precedents that have led to necrotic civilization, in which severe damage to one essential system leads to secondary damage to other systems, causing a “cascade of effects”. Necrotic civilization is an ugly show. It arises from ossified states of domination of the Anthropocene, it is based on a lack of proper care, and as it spreads, it releases harmful effects that damages everything around it. As larvae of a post-human era, we effect care, to remake ourselves in the biotic ecocentrism of the larvalscene. Death is not the opposite of life. Many deaths have passed, and many are to come, deaths of more of our languages, of some of our identities, ways of life, comforts, hopes and ideals, of our embodied selves, our non-human kin, our planetary world and world-ed planet. But astride this destructive necrosis are other possible deaths, occurring as a disruptive poesis and an infectious refusal – deaths of unitary truth and stasis that deny our perpetual becoming outside of reason and rationality. These are the deaths we can risk to generate a biotic ecocentrism beyond necrosis.

This brings me to the Young Lungs Research Series – a laboratory providing funding, space and support for research and exchange. Research, for artists, is rarely funded, at least in my experience. But research is critical to an artistic practice, it is in expansion, not product, that a practice grows. The four artists groups in this series intermingled challenges to norms of social relations and dynamics – themes interrogated from different positionality by Frantz Fanon, Erving Goffman and Elizabeth Grosz. Fanon focuses, in Black Skin, White Masks on the oppression, forced masking and destructive alienation of Blackness in a white supremacist world designed for the benefit of others. Goffman, in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, focuses on the dramaturgical perspective of social scripting and impression management in everyday life – which in contemporary techno-culture, multiplies exponentially online – Instagram anyone? Or are you too busy photoshopping your feed? In Volatile Bodies, Grosz challenges dualistic binaries by interweaving the internal/external through the model of the Mobius Strip. All of the artists spoke of going beyond technique and training, false authenticity, curated interactions and illusions of control.

Carol-Ann Bohrn’s project was done in collaboration with Madeline Rae, the two met in Ace Art’s Cartae School. The work centered on dichotomies between the subjective inner self and the performance of self in the social sphere. Through this research, Bohrn shared deliberately clumsy articulate and inarticulate embodied and verbal dissonance that demanded: where does the social front negate or support internal subjectivity, where does it mirror, and where does it reshape interiority while risking intolerable alienation?

Sometimes concordant, other times discordant, her movement and speech rode the Mobius Strip inside to outside to inside to outside as a continual loop, because rather than being dichotomous we are pluralities. But it’s painfully hilarious isn’t it – to witness your own shameful accommodations rendered materially visible. We live in sociality, managing varying histories of trauma, and if you thought Bohrn and Rae were going to provide some neatly packaged resolution of the resultant complex conflicts that arise, think again.

Zorya Arrow began with an exploration of intimacy by experimenting with 1 on 1 performances to explore the relationship between performer and audience. But for her this raised antagonisms of expectation that proved to be unproductive. How else to find out, how does who is there, in the how is there, determine the outcome of what is there.

But the difficulties of entering the unknown by not doing the same doing that threatens to become a pattern or a predictable trajectory, led her to instead invite the audience literally behind the curtain to witness her disposition.

Delf Gravert shared WALRUS, I AM, which arose during time he spent in the North. His research raises pressing epistemological questions of what is valorized in ways of knowing – the oral, the textual – and beyond those binaries, the physical, the sonic and other senses? What is a staged work, what is the structure, why do you behave as an audience and who is there to see it – is it the embodied presences in the room, or can we operate multi-dimensionally and recognize we are multitudes of generations of relations that are always, already, in the room.

Delf comes at the questions of affective states and emotive reasoning relentlessly, with uncanny idiosyncratic physicality and humor that at one point explodes in his scream – “I don’t know fuck all!” Well how about that, neither do we.

Andrew Henderson and Eroca Nicols, close friends and co-creators, faced the life altering moment of Glamdrew Andrew’s terminal diagnosis with beautiful courage, bringing Eroca’s study and practice of death rituals to create a Living Funeral as a queer monument to an embracing of that which for most remains shamefully unspeakable.

With collaborators Carly Boyce and Mars Gradiva, they created a joyful and inclusive space challenging cultural denials of death, creating magic in an atmosphere of loving generosity that opened public conversations around death, not only in the performance but broadly through extensive media coverage. It is from our conversations of delusional denial, of how it is ‘A Big Mess,’ that the title of this talk came to be. Andrew Henderson died on Wednesday October 26th.

We are a mess, in a big mess, and current sense-making makes no sense as it forecloses possibility. Creativity unconfined can provide artists the platform to disrupt necrotic sense making, to displace the self and selves, to reinscribe our bodies and then infect others with a refusal, so creation can live aside so much cessation.

I end with the work of Andrew Henderson, Eroca Nicols and collaborators Carly and Mars because they created a performance of consummate generosity – and I think it was covered extensively in the media as it provided a broad and enticing invitation to bring forth a self beyond ordinary sense-making, reaffirming the profound place of love and care, where our shameful secrets and living deaths can go to the grave and we can begin again.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carrington, Damian. “World on Track to Lose Two-Thirds of Wild Animals by 2020, Major Report Warns.” The Guardian, 27 October, 2016.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skins, White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1967.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books, 1959.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Larval Rock Stars. Chrysalis. Praba Pilar and Anuj Vaidya. < https://larvalrockstars.wordpress.com/>

Mooney, Chris. “What the ‘sixth extinction’ will look like in the oceans: The largest species die off first.” The Washington Post, 14 September 2016.

Pilar, Praba. Photographs of performers taken in Winnipeg, Canada. 2016.

Sarson, Janet. Photograph of Praba Pilar in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. 2010.

Stanford University. “Sixth mass extinction is here: Humanity’s existence threatened.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 19 June 2015.

Zalasiewizc, Jan. “The Earth Stands on the Brink of its Sixth Mass Extinction and the Fault is Ours.” The Guardian, 21 June, 2015. < https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jun/21/mass-extinction-science-warning>